Science and Theism by Sebastian Mahfood, PhD

Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, OP, serves as Vice-President of Administration at Holy Apostles College & Seminary in Cromwell, CT, Provost of the Sacred Heart Institute for the Ongoing Formation of Clergy in Huntington, NY, Director of the Catholic Distance Learning Network of the National Catholic Educational Association's Seminary Department, and secretary of the board of the Institute for Theological Encounter with Science and Technology. He is an Adler-Aquinas Fellow, a member of Georgetown University’s Delta Phi Epsilon Foreign Service Fraternity, and a Lay Dominican of the Queen of the Holy Rosary Chapter in the Province of St. Albert the Great. He holds a doctorate in postcolonial literature and theory from Saint Louis University along with several master’s degrees in the fields of comparative literature, philosophy, theology, and educational technology. Among his publications include his book on African narrative socialism entitled Radical Eschatologies: Embracing the Eschaton in the Works of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Nuruddin Farah, and Ayi Kwei Armah. He lives in St. Louis with his wife, Dr. Stephanie Mahfood, and children, Alexander and Eva Ruth.

Note from Dr. Chervin: This chapter is part of another book I have been writing with Dr. Mahfood called Catholic Realism: Key to the Refutation of Atheism and Evangelizing Atheists. I asked my coauthor to allow this chapter to also be part of Toward a 21st Century Catholic World-View.

Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, OP, serves as Vice-President of Administration at Holy Apostles College & Seminary in Cromwell, CT, Provost of the Sacred Heart Institute for the Ongoing Formation of Clergy in Huntington, NY, Director of the Catholic Distance Learning Network of the National Catholic Educational Association's Seminary Department, and secretary of the board of the Institute for Theological Encounter with Science and Technology. He is an Adler-Aquinas Fellow, a member of Georgetown University’s Delta Phi Epsilon Foreign Service Fraternity, and a Lay Dominican of the Queen of the Holy Rosary Chapter in the Province of St. Albert the Great. He holds a doctorate in postcolonial literature and theory from Saint Louis University along with several master’s degrees in the fields of comparative literature, philosophy, theology, and educational technology. Among his publications include his book on African narrative socialism entitled Radical Eschatologies: Embracing the Eschaton in the Works of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Nuruddin Farah, and Ayi Kwei Armah. He lives in St. Louis with his wife, Dr. Stephanie Mahfood, and children, Alexander and Eva Ruth.

Note from Dr. Chervin: This chapter is part of another book I have been writing with Dr. Mahfood called Catholic Realism: Key to the Refutation of Atheism and Evangelizing Atheists. I asked my coauthor to allow this chapter to also be part of Toward a 21st Century Catholic World-View.

Introduction

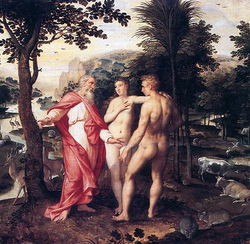

That science is limited is due to the fact that it deals with nothing more than material creation. Everything it measures, then, is only that which is manifest in some way within the realm of the senses. For that reason, science has no way to disprove the immeasurable, no way to discount philosophy or metaphysical realities that are purely spiritual. Science is not without its importance, however. What science can do is provide us with demonstrations of causality. Some effect lies before us as a fait accompli, and its very presence is suggestive of some causal agent that brought it about. Our own presence here is a case in point since the body, as Blessed John Paul II has said, is the sign of the person. As material beings, we can identify in the presence of one another a material cause, but we are also spiritual beings created in the image and likeness of God, which means we can identify in our communion with one another a formal cause.

That science is limited is due to the fact that it deals with nothing more than material creation. Everything it measures, then, is only that which is manifest in some way within the realm of the senses. For that reason, science has no way to disprove the immeasurable, no way to discount philosophy or metaphysical realities that are purely spiritual. Science is not without its importance, however. What science can do is provide us with demonstrations of causality. Some effect lies before us as a fait accompli, and its very presence is suggestive of some causal agent that brought it about. Our own presence here is a case in point since the body, as Blessed John Paul II has said, is the sign of the person. As material beings, we can identify in the presence of one another a material cause, but we are also spiritual beings created in the image and likeness of God, which means we can identify in our communion with one another a formal cause.

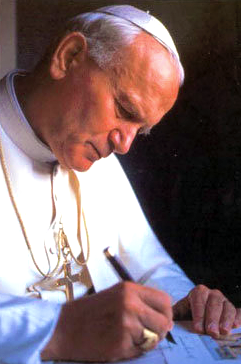

Evidence of this, in fact, may be found our being persons of communion. “That man should speak is nature’s own behest,” our great ancestor Adam is made to say in the eighth sphere of Dante’s Paradiso, “but that you speak in this way or that/ nature lets you decide as you think best” (Canto XXVI, 130-2). The same is true with our science—that we pursue the mechanics of this world with wonder is in our nature; the manner in which we do it is up to us. It is far better to have a manner resonant with our nature than it is to have one that is out of joint with it. That is how this chapter addresses the question of Catholic realism—by showing that science and theism are mutually supportive of one another when we understand their roles. “Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.” Pope John Paul II, June 1, 1988, letter to Rev. George V. Coyne, SJ, Director of the Vatican Observatory. [1]

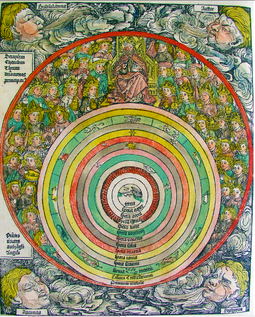

| A millennium before Galileo, the Church had accepted this nostrum, which has been attributed to St. Augustine, that the book of nature and the book of Scripture were both written by the same Author, and they will not be in conflict when properly read and interpreted. Our new translation of the Nicene Creed confirms this, in part, where we say, “Creator of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.” |

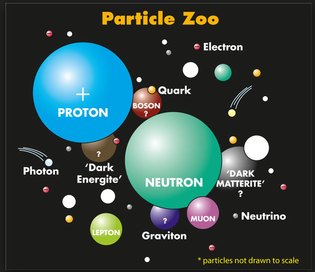

This visible world, according to Dr. Tom Sheahen, director of the Institute for Theological Encounter with Science and Technology, is the world science can access, with microscopes and telescopes, etc. It occupies space and time and is made out of atoms. This is where sciences like physics contribute. But there is an ‘invisible’ part of creation, which has been revealed to us in Scripture. Humans have access to a portion of this. It's a mistake to think science comprehends it.

The visible and the invisible things, precisely because both were created by God, enable parallel and complementary paths toward him. Concerning the visible things, Aristotle wrote in his Metaphysics, “All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses.” Pope Benedict XVI, in an address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences on October 28, 2010, said, "The Church is convinced that scientific activity ultimately benefits from the recognition of man’s spiritual dimension and his quest for ultimate answers that allow for the acknowledgement of a world existing independently from us, which we do not fully understand and which we can only comprehend in so far as we grasp its inherent logic. Scientists do not create the world; they learn about it and attempt to imitate it, following the laws and intelligibility that nature manifests to us."[2]

The visible and the invisible things, precisely because both were created by God, enable parallel and complementary paths toward him. Concerning the visible things, Aristotle wrote in his Metaphysics, “All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses.” Pope Benedict XVI, in an address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences on October 28, 2010, said, "The Church is convinced that scientific activity ultimately benefits from the recognition of man’s spiritual dimension and his quest for ultimate answers that allow for the acknowledgement of a world existing independently from us, which we do not fully understand and which we can only comprehend in so far as we grasp its inherent logic. Scientists do not create the world; they learn about it and attempt to imitate it, following the laws and intelligibility that nature manifests to us."[2]

This provides the context for the transition to the invisible things. The scientist’s experience as a human being is therefore that of perceiving a constant, a law, a logos that he has not created but that he has instead observed: in fact, it leads us to admit the existence of an all-powerful Reason, which is other than that of man, and which sustains the world. This is the meeting point between the natural sciences and religion. As a result, science becomes a place of dialogue, a meeting between man and nature and, potentially, even between man and his Creator. [3]

The potential dialogue that exists here between man and his Creator becomes an actual dialogue when man pursues his science by seeing the Creator as the cause of the created thing. Each new thing we learn, then, magnifies our understanding of the glory of God on whom we are able to gaze with increasing wonder at his sense of order, harmony, and design. The beauty of the natural world attracts us, and what is drawn toward beauty is drawn toward the reality of the person who made it. After all, while we learn about the world and come to know it through its effects, we do not create it; rather, it is created by God who knows it as its cause.

The potential dialogue that exists here between man and his Creator becomes an actual dialogue when man pursues his science by seeing the Creator as the cause of the created thing. Each new thing we learn, then, magnifies our understanding of the glory of God on whom we are able to gaze with increasing wonder at his sense of order, harmony, and design. The beauty of the natural world attracts us, and what is drawn toward beauty is drawn toward the reality of the person who made it. After all, while we learn about the world and come to know it through its effects, we do not create it; rather, it is created by God who knows it as its cause. To begin to bring about an understanding of the relationship between faith and science, then, what is needed is a framework that advances the concept of causality, which Aristotle defines simply as that which brings something else about and is its reason for being. Aristotle explains that four causes exist, namely the formal cause, the efficient cause, the material cause and the final cause. The formal cause is the kind of thing something is. A cat, for instance, has a particular form that distinguishes it from a dog, and this form is predicated on the specific difference (the thing that makes something one species and not another). The specific difference identifies a thing’s nature, so we can speak in terms of the common nature of a cat or of a dog. The efficient cause is that which initiates a thing’s coming into existence. The study of an efficient cause is necessarily, then, the study of agency, of an identifiable being that brought something else into being. The material cause is the “stuff” of which something is made. The material cause of this chapter presently on the screen, for instance, is pixel and plastic. The final cause is the end for which something is made, the purpose, that is, of a thing. It is easy to identify the purpose, or a range of purposes, for any given object. Even if people differ on their understanding of a thing’s purpose, they will agree that a given object in their hand has some purpose as demonstrated by their using it, as Marshal McLuhan demonstrated in his study of our technologies as an extension of our persons. Every person, place, event and thing (that is, all nouns) is explainable in terms of all four causes.

While the theist would say that the explanation of all four causes is necessary for all things, material reductionists consider only the efficient and material causes as valid. The materially reductive mentality, further, considers the efficient cause only in natural terms. A framework for refuting anyone, particularly atheists, who believe that only efficient and material causes are valid is to advance the understanding not only do we need to know that all four causes are necessary for a complete comprehension of a thing, but that we also need to know that agency, the efficient cause, is both a natural and a supernatural phenomenon. God allows, after all, secondary causes as St. Thomas explains,

Two things belong to providence--namely, the type of the order of things foreordained towards an end; and the execution of this order, which is called government. As regards the first of these, God has immediate providence over everything, because He has in His intellect the types of everything, even the smallest; and whatsoever causes He assigns to certain effects, He gives them the power to produce those effects. Whence it must be that He has beforehand the type of those effects in His mind. As to the second, there are certain intermediaries of God's providence; for He governs things inferior by superior, not on account of any defect in His power, but by reason of the abundance of His goodness; so that the dignity of causality is imparted even to creatures. (emphasis ours, ST I, Q. 22, Art. 3) Or, more concisely, God's immediate provision over everything does not exclude the action of secondary causes; which are the executors of his order, as was said above (19, 5, 8). (ST I, Q. 22, Art. 3, ad. 2)

Our establishing only these two things, then, knowledge of the necessity of the four causes and an understanding that efficient causes need to be thought of as both natural and supernatural, provides the frame on which all other things can hang. The reason is that it allows us to then posit, for instance, that every physical object has a natural origin but that our cosmology points to a first, non-material cause, predicated by the question, where did the matter of which that physical object is composed come from? The question arises because all matter is contingent as evidenced by the fact that it changes. Any contingent being requires an agent, or causal being, to bring it about, and natural options, precisely because they are natural, can be only intermediary, not the ultimate, source of a thing’s being.

Once we agree that a thing has an efficient cause that is also supernatural, it is not that far of a leap for us to understand that it has a final cause to which its form and matter are oriented so that all its causes work together in the realization of the thing’s purpose. If we were to make a tool, we would do so with our end in mind, and that end would cause that tool to take a certain kind of form and be made with a certain kind of material so that its cause (its efficient cause) could create it for the purpose it was intended. It is no different with the human person, who is created for a certain end (two, since a human person is made for both natural and supernatural happiness), and whose soul is so made that it can form a body from organic matter that has the capacity to glorify God with its life.

Scholastic Science

The medieval period in European history can be characterized as having taken place between the age where the study of philosophy was unencumbered by Divine revelation and the age where the study of philosophy sought independence from Divine Revelation. In that long period of philosophical Scholasticism, stretching from the life of Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius (AD 480–524 or 525 ), who brought the philosophy of Aristotle into Christendom in his many translation efforts, one of which was Porphyry’s Isagoge, an introduction to Aristotle’s Categories, which provided the framework for Aristotle’s Physics, to the death of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), Christian philosophers sought to reconcile faith and reason.4 Muslim philosophers, too, sought this kind of reconciliation in a period of activity extending from the life of Al-Kindi (c. 801–873) to the death of Ibn Rushd (1128–1198), but Islam called its pursuit in this area a Golden Age, and its catalog of accomplishments enabled, in part, the Christian European Renaissance. [5]

To advance the discussion to faith-supported advancement in science, the Islamic world during its scholastic period provides us with an excellent example of scientific advances guided by a theocentric worldview. By the time of the European Renaissance, Muslim advancements in science and technology had dwarfed those of Europe for four centuries. Christian Europe, on the other hand, pursued most of its scientific advancements following its scholastic period under an increasingly anthropocentric and materially reductionist worldview that slouched toward and finally fell into solipsism. [6] Robert Augros and George Stanciu address this Western worldview in their book The New Story of Science (1984) when they explain what they mean by the Old Story of Science, “that there was in the 17, 18, and 19 centuries the gradual building up of a world view in physics and cosmology that was progressively more materialistic” (p. ix).

The Muslims proved over a thousand years ago that a resurgence of an authentic intellectual tradition—one, that is, that pursues the relationship between faith and science—would benefit from a return to a strong faith tradition because our understanding of created things requires a concomitant understanding of the ultimate source of their creation. This is not to say that we have not made significant advances in science and technology during the modern period (which in Church history is defined as the years between 1274 and the present day), but that those advances have not necessarily been oriented to our loving God with all our heart, soul, strength, and mind, or in loving our neighbor as ourselves (Luke 10:27).

In pursuit of the relationship between faith and reason, John Paul II begins his encyclical letter Fides et Ratio (1998), "Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth; and God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth—in a word, to know himself—so that, by knowing and loving God, men and women may also come to the fullness of truth about themselves." [7]

The medieval period in European history can be characterized as having taken place between the age where the study of philosophy was unencumbered by Divine revelation and the age where the study of philosophy sought independence from Divine Revelation. In that long period of philosophical Scholasticism, stretching from the life of Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius (AD 480–524 or 525 ), who brought the philosophy of Aristotle into Christendom in his many translation efforts, one of which was Porphyry’s Isagoge, an introduction to Aristotle’s Categories, which provided the framework for Aristotle’s Physics, to the death of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), Christian philosophers sought to reconcile faith and reason.4 Muslim philosophers, too, sought this kind of reconciliation in a period of activity extending from the life of Al-Kindi (c. 801–873) to the death of Ibn Rushd (1128–1198), but Islam called its pursuit in this area a Golden Age, and its catalog of accomplishments enabled, in part, the Christian European Renaissance. [5]

To advance the discussion to faith-supported advancement in science, the Islamic world during its scholastic period provides us with an excellent example of scientific advances guided by a theocentric worldview. By the time of the European Renaissance, Muslim advancements in science and technology had dwarfed those of Europe for four centuries. Christian Europe, on the other hand, pursued most of its scientific advancements following its scholastic period under an increasingly anthropocentric and materially reductionist worldview that slouched toward and finally fell into solipsism. [6] Robert Augros and George Stanciu address this Western worldview in their book The New Story of Science (1984) when they explain what they mean by the Old Story of Science, “that there was in the 17, 18, and 19 centuries the gradual building up of a world view in physics and cosmology that was progressively more materialistic” (p. ix).

The Muslims proved over a thousand years ago that a resurgence of an authentic intellectual tradition—one, that is, that pursues the relationship between faith and science—would benefit from a return to a strong faith tradition because our understanding of created things requires a concomitant understanding of the ultimate source of their creation. This is not to say that we have not made significant advances in science and technology during the modern period (which in Church history is defined as the years between 1274 and the present day), but that those advances have not necessarily been oriented to our loving God with all our heart, soul, strength, and mind, or in loving our neighbor as ourselves (Luke 10:27).

In pursuit of the relationship between faith and reason, John Paul II begins his encyclical letter Fides et Ratio (1998), "Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth; and God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth—in a word, to know himself—so that, by knowing and loving God, men and women may also come to the fullness of truth about themselves." [7]

As we continue through the second decade of the twenty-first century, especially, we find compelling reasons to articulate once again this relationship between faith and reason, and we can do this by reaching into the Western European intellectual tradition and relying upon the method used during the Islamic Golden Age. One of the most compelling of these reasons is refuting in a real way the rise of the New Atheism that, according to Scott Hahn and Benjamin Wiker, seeks the political power it needs to advance the culture of death identified in Evangelium Vitae by Blessed John Paul II. [8,9]

It is only when we have fully grasped this relationship between our theology and our science, indeed, that our arts will flourish with a truer purpose than they have long known. Philosophy, which at its core is the thought process of a human person contemplating the source of all created being, is necessarily a spiritual activity, for it is the exercise of the rational faculties, of the immaterial part of humankind. It is the very kind of activity, in fact, that enables us to transcend our material existence. For a philosopher to say that everything is material is, therefore, absurd, for in the very process of articulating that concept, the concept itself is negated. A proper philosophical anthropology is instructive on this point. [10] Essentially, the soul is a spiritual thing in a composite relationship with the matter that it forms.

To think that matter is “all that matters” is to limit ourselves significantly. If we are composite beings, then that reality brings about a particular way of looking at the world. We find, namely, that a relationship exists between material and immaterial things and that some immaterial things that cannot be known by our senses or our intellects and have been, consequently, revealed to us by a Person who is our Creator. This is the essence of Christian theism, which is a faith seeking understanding, to quote St. Anselm. If we are going to make headway on understanding who we are and what we are doing as we interact with the material world in which we find ourselves, we have, consequently, to approach our search for understanding in the attitude of faith rather than in the attitude of skepticism. What we want to do is reclaim Scholasticism, not as defined through the lens of the Enlightenment that has informed so much of modernity, but through its own understanding of itself, an understanding that is apparent in what the Muslims did with it in terms of advancing the principles of science through the strength of their faith.

It is only when we have fully grasped this relationship between our theology and our science, indeed, that our arts will flourish with a truer purpose than they have long known. Philosophy, which at its core is the thought process of a human person contemplating the source of all created being, is necessarily a spiritual activity, for it is the exercise of the rational faculties, of the immaterial part of humankind. It is the very kind of activity, in fact, that enables us to transcend our material existence. For a philosopher to say that everything is material is, therefore, absurd, for in the very process of articulating that concept, the concept itself is negated. A proper philosophical anthropology is instructive on this point. [10] Essentially, the soul is a spiritual thing in a composite relationship with the matter that it forms.

To think that matter is “all that matters” is to limit ourselves significantly. If we are composite beings, then that reality brings about a particular way of looking at the world. We find, namely, that a relationship exists between material and immaterial things and that some immaterial things that cannot be known by our senses or our intellects and have been, consequently, revealed to us by a Person who is our Creator. This is the essence of Christian theism, which is a faith seeking understanding, to quote St. Anselm. If we are going to make headway on understanding who we are and what we are doing as we interact with the material world in which we find ourselves, we have, consequently, to approach our search for understanding in the attitude of faith rather than in the attitude of skepticism. What we want to do is reclaim Scholasticism, not as defined through the lens of the Enlightenment that has informed so much of modernity, but through its own understanding of itself, an understanding that is apparent in what the Muslims did with it in terms of advancing the principles of science through the strength of their faith.

The Catholic Church: Leading from the Front

In The Phenomenon of Man, Fr. Teilhard de Chardin, the priest who came up with the idea that one day our technologies would connect every one of us with one another for the purpose of strengthening our relationship with Christ, writes,

After close on two centuries of passionate struggles, neither science nor faith has succeeded in discrediting its adversary. On the contrary, it becomes obvious that neither can develop normally without the other. And the reason is simple: the same life animates both. Neither in its impetus nor its achievements can science go to its limits without becoming tinged with mysticism and charged with faith.

This realization is a kind of intellectual time bomb set to go off sometime during the twenty-first century as the chasm initiated by people like René Descartes that separated the pursuit of an understanding of the natural world from the pursuit of an understanding of the supernatural world starts to be spanned in the popular consciousness.

The natural world, after all, was understood by Aristotle and the scholastic philosophers who followed him to be the first level of abstraction, that is, the level of material being where things like earth, fire, water, and air (in fact, all material phenomena—wood, for instance, and bricks) were manifest to the sensory perceptions. Anything that we can see, hear, feel, touch, or taste falls into the realm of this first level of abstraction. It is the realm that most of us understand because we can apply our senses to it in a meaningful way that allows us to develop a percept that can be transformed by our minds into a universal concept. We have to touch fire only once, for instance, before we get the universal concept of “hotness.” After that experience, the sight of any fire will be a signal to us to avoid coming into contact with it. When a child holds a magnet and attracts a paper clip, furthermore, he or she “gets” the concept of attraction, that some things by their very nature are attracted to other things due to the nature of those things.

While the concept of attraction is highly applicable in the visible world, it is also applicable in the invisible world, which, after all, was understood by Aristotle and the scholastic philosophers who followed him to be the third level of abstraction, that is, the level of immaterial being where things like God, angels, and departed human souls are not manifest to the sensory perceptions. This is the spiritual realm, the realm in which faith is required, faith, which Hebrews 11:1 defines as “evidence of things not seen; the substance of things hoped for.” Because we cannot see them, the materialist would argue, they simply cannot exist, and the kind of philosophical anthropology (like that of Sigmund Freud) that argues for the existence of a material soul denies any practical value of faith and hope. The fullness of truth expressed in Catholic Realism is that we are drawn by love. We are attracted to it in a real and palpable way, and the source of that attraction is none other than God, the person who brought us into being for our own sake to live in eternal communion with him. Our exploring the world that teaches us all sorts of things about its Creator is the most fundamental way we can discover him.

In The Phenomenon of Man, Fr. Teilhard de Chardin, the priest who came up with the idea that one day our technologies would connect every one of us with one another for the purpose of strengthening our relationship with Christ, writes,

After close on two centuries of passionate struggles, neither science nor faith has succeeded in discrediting its adversary. On the contrary, it becomes obvious that neither can develop normally without the other. And the reason is simple: the same life animates both. Neither in its impetus nor its achievements can science go to its limits without becoming tinged with mysticism and charged with faith.

This realization is a kind of intellectual time bomb set to go off sometime during the twenty-first century as the chasm initiated by people like René Descartes that separated the pursuit of an understanding of the natural world from the pursuit of an understanding of the supernatural world starts to be spanned in the popular consciousness.

The natural world, after all, was understood by Aristotle and the scholastic philosophers who followed him to be the first level of abstraction, that is, the level of material being where things like earth, fire, water, and air (in fact, all material phenomena—wood, for instance, and bricks) were manifest to the sensory perceptions. Anything that we can see, hear, feel, touch, or taste falls into the realm of this first level of abstraction. It is the realm that most of us understand because we can apply our senses to it in a meaningful way that allows us to develop a percept that can be transformed by our minds into a universal concept. We have to touch fire only once, for instance, before we get the universal concept of “hotness.” After that experience, the sight of any fire will be a signal to us to avoid coming into contact with it. When a child holds a magnet and attracts a paper clip, furthermore, he or she “gets” the concept of attraction, that some things by their very nature are attracted to other things due to the nature of those things.

While the concept of attraction is highly applicable in the visible world, it is also applicable in the invisible world, which, after all, was understood by Aristotle and the scholastic philosophers who followed him to be the third level of abstraction, that is, the level of immaterial being where things like God, angels, and departed human souls are not manifest to the sensory perceptions. This is the spiritual realm, the realm in which faith is required, faith, which Hebrews 11:1 defines as “evidence of things not seen; the substance of things hoped for.” Because we cannot see them, the materialist would argue, they simply cannot exist, and the kind of philosophical anthropology (like that of Sigmund Freud) that argues for the existence of a material soul denies any practical value of faith and hope. The fullness of truth expressed in Catholic Realism is that we are drawn by love. We are attracted to it in a real and palpable way, and the source of that attraction is none other than God, the person who brought us into being for our own sake to live in eternal communion with him. Our exploring the world that teaches us all sorts of things about its Creator is the most fundamental way we can discover him.

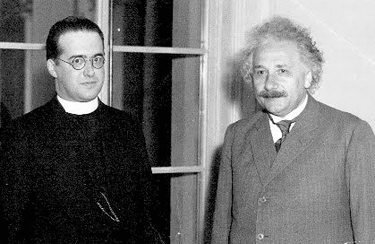

Fr. Georges LeMaitre & Albert Einstein

Fr. Georges LeMaitre & Albert Einstein Scientific truths, of course, like philosophical truths, are not meant to replace articles of faith. They do, however, contribute to our praise of God. In 2012, Dr. Tom Sheahen did a short survey of a few advances of the past hundred years, the span of time put forth by Augros and Stanciu as “the new story of science,” in an article entitled “Scientific Theories,” which starts with the Jewish Albert Einstein, who did not believe in a personal God, qualifying what he did believe as follows:

"My religion consists of a humble admiration of the illimitable superior spirit who reveals himself in the slight details we are able to perceive with our frail and feeble minds. That deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a superior reasoning power, which is revealed in the incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God."

Sheahen ends with the Catholic Fr. George LeMaitre:

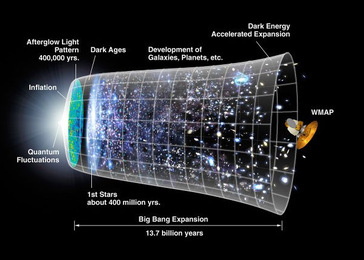

In 1912, we had no idea of separate galaxies. There were some fuzzy objects out there, but telescopes weren't good enough to resolve what they actually were. Astronomy was still a fascinating field, but there was not yet a field of cosmology. Then along came Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, which was a comprehensive theory uniting space and time and gravity. Einstein's theory was totally different from what people had previously assumed. But Einstein's previous theoretical accomplishments (four important new theories in 1905) assured that many scientists at least paid attention. By 1918, a prediction of Einstein's theory was verified via an experiment conducted during a solar eclipse, and that greatly enhanced the credibility of General Relativity.

"My religion consists of a humble admiration of the illimitable superior spirit who reveals himself in the slight details we are able to perceive with our frail and feeble minds. That deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a superior reasoning power, which is revealed in the incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God."

Sheahen ends with the Catholic Fr. George LeMaitre:

In 1912, we had no idea of separate galaxies. There were some fuzzy objects out there, but telescopes weren't good enough to resolve what they actually were. Astronomy was still a fascinating field, but there was not yet a field of cosmology. Then along came Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, which was a comprehensive theory uniting space and time and gravity. Einstein's theory was totally different from what people had previously assumed. But Einstein's previous theoretical accomplishments (four important new theories in 1905) assured that many scientists at least paid attention. By 1918, a prediction of Einstein's theory was verified via an experiment conducted during a solar eclipse, and that greatly enhanced the credibility of General Relativity.

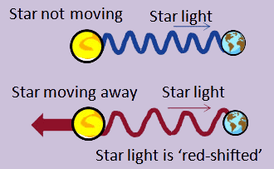

Soon many more scientists got interested, because it was possible to associate the huge amount of observed astronomical data with a theory that made sense of it all. The measurable difference in light arriving from some very distant stars (the “red shift”) provided convincing evidence that the universe was expanding—and that begged for an explanation. Einstein's equations of general relativity involved tensor calculus, which was unfamiliar to most scientists at the time, but a few set out to solve those equations for special conditions of the universe. Einstein, who once said, “I want to know God's thoughts...the rest are details,” himself believed that the universe was in a “steady state,” hardly changing at all.

Around 1922, a Russian named Alexander Friedmann worked out a solution for a universe expanding from a singular starting point; unfortunately, he died soon thereafter and his work wasn't noticed. Working independently, Georges LeMaitre, a Belgian Catholic priest, solved Einstein's equations for a universe starting at time t = 0 and expanding from a singular point to its present size. He turned that in as his doctoral thesis to both Harvard and M.I.T. in 1925, and that was quickly noticed in the western scientific world. When Einstein heard of LeMaitre's work, he scoffed at it; and that disdain put LeMaitre into an uphill struggle. The impression of a steady unchanging universe “out there” was very strong in those days, and the thought of everything starting off at a single point was incomprehensible to most physicists. Other critics sneeringly invented the phrase “big bang” to pile on the ridicule.

The disdain for LeMaitre didn't last long. Better telescopes were built, and other galaxies beyond our own Milky Way were found. By 1929, Edwin Hubble's observations permitted a calculation of how fast the universe was expanding, and it was all consistent with LeMaitre's theory. Einstein himself eventually came to agree with LeMaitre—for the simple and honorable scientific reason that LeMaitre's theoretical solution accounted for the data. Einstein's theory of general relativity, meanwhile, became fully accepted throughout the scientific world. With his scientific respectability secure, LeMaitre moved into higher circles within the Catholic Church, and became a key scientific advisor to Pope Pius XII. In 1950, a most interesting backstage drama took place, which shows what real scientists think about even the best scientific theories.

Pope Pius XII saw that the big bang theory coincided very nicely with the narrative in Chapter one of the Book of Genesis, and was going to declare it to be true, a doctrine of faith. Obviously that would have been a huge accolade for LeMaitre, a permanent vindication of his theory. Instead of rejoicing at this, LeMaitre himself talked the Pope out of it. LeMaitre explained that no theory in physics, however elegant or reliable, is truly final. Every theory can always be revised; every theory can be contradicted (and thereby destroyed) by a single experiment. LeMaitre knew his history well: only a century earlier, “the ether” seemed a sure thing.

In 1963, new evidence from radio astronomy gave further evidence that indeed the universe originated in a sudden explosion, and the competing “steady state” theory was abandoned. The big bang became the only game in town. However, with the passage of yet another half-century, recent observations have indicated that some correction may be necessary to Einstein's theory: there may well be some additional force (customarily termed “dark energy”) that causes the expansion of the universe to accelerate. In the years ahead, will general relativity or the big bang be corrected? Stay tuned.

It is enormously to the credit of Fr. Georges LeMaitre that he stood up to sustain the independence of science and religion. LeMaitre had an enduring confidence that both science and religion are complementary pathways to knowledge, but scientific theories can stand or fall on their own, and don't need religion to referee. As Albert Einstein said, "Science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind." More recently (1987), Pope John Paul II stated their complementary relationship very cogently: “Science can purify religion from error and superstition. Religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.”

It is enormously to the credit of Fr. Georges LeMaitre that he stood up to sustain the independence of science and religion. LeMaitre had an enduring confidence that both science and religion are complementary pathways to knowledge, but scientific theories can stand or fall on their own, and don't need religion to referee. As Albert Einstein said, "Science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind." More recently (1987), Pope John Paul II stated their complementary relationship very cogently: “Science can purify religion from error and superstition. Religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.”

Conclusion

What we need to pursue is the restoration of the friendship between scientists and theologians who are both pursuing the same truth—the nature of the world in relation to its Source. For the materialist, that source is natural, and it dead-ends in the ephemeral material world. For the realist, that Source is supernatural, and it is God. Our science and our philosophy should point to the ultimate source of being, and we cannot find that in anything ephemeral—only in that which is eternal, in that which is God.

The relationship between faith and science takes an interesting turn in an era where New Atheists like biologist Richard Dawkins seem to be gaining ground in their fight against faith-based thinking. It may be important to remember that there was a time when Christian faith was not an issue in philosophy and science. Philosophers like Aristotle and scientists like Archimedes seemed to get along fine without it, each reaching the apex of achievement in their respective fields.

The question posed by the atheists and the New Atheists on whether our reliance on God somehow diminishes our understanding of our own value as human persons and our own capacity for intellectual acuity is really a non-question. We already know we are temporally finite because our bodies die over time, and we already know we are limited as evidenced by a myriad of factors, not the least of which involves failing memories and various incapacities in our ability to understand the fullness of the disciplines that lie remote from our own.

It actually increases our understanding of our own value as human persons to know that an infinite being, a necessary being, cared enough for finite, contingent beings such as us that he brought us into being in the first place and has reserved for us an eternal destiny in joyful communion with him if that is our choice. It actually increases our understanding of our intellectual acuity if we know that the light of our understanding has a source beyond our own limited intellects toward which we can strive.

What we need to pursue is the restoration of the friendship between scientists and theologians who are both pursuing the same truth—the nature of the world in relation to its Source. For the materialist, that source is natural, and it dead-ends in the ephemeral material world. For the realist, that Source is supernatural, and it is God. Our science and our philosophy should point to the ultimate source of being, and we cannot find that in anything ephemeral—only in that which is eternal, in that which is God.

The relationship between faith and science takes an interesting turn in an era where New Atheists like biologist Richard Dawkins seem to be gaining ground in their fight against faith-based thinking. It may be important to remember that there was a time when Christian faith was not an issue in philosophy and science. Philosophers like Aristotle and scientists like Archimedes seemed to get along fine without it, each reaching the apex of achievement in their respective fields.

The question posed by the atheists and the New Atheists on whether our reliance on God somehow diminishes our understanding of our own value as human persons and our own capacity for intellectual acuity is really a non-question. We already know we are temporally finite because our bodies die over time, and we already know we are limited as evidenced by a myriad of factors, not the least of which involves failing memories and various incapacities in our ability to understand the fullness of the disciplines that lie remote from our own.

It actually increases our understanding of our own value as human persons to know that an infinite being, a necessary being, cared enough for finite, contingent beings such as us that he brought us into being in the first place and has reserved for us an eternal destiny in joyful communion with him if that is our choice. It actually increases our understanding of our intellectual acuity if we know that the light of our understanding has a source beyond our own limited intellects toward which we can strive.

If we know that an eternal, perfect Being created us and has a plan for our salvation, then the most reasonable thing to do is to rely on that Being to provide us with the grace to achieve it. For this reason, we individual substances of a rational nature must cultivate an understanding of the relationship between ourselves and our Creator. Those of us who are not Pelagians have to ask ourselves the very simple question—what good is the exercise of our reason if it is insufficient by itself to save us?

The short answer is that faith and reason cooperate with one another in our understanding who we are—our identity—which is most perfectly revealed by Christ himself who fully reveals mankind to himself. They are the two wings about which Christ spoke to St. Catherine of Siena as recorded by St. Raymond of Capua when he said, "You have two feet to walk and two wings to fly." With both these wings in flight, we are buoyed up by God's love.

Even so, we yet hit a limitation. As strong as we are created in the image and likeness of God whose natural law is written on our hearts, we need supernatural grace to perfect our natural gifts, and God provides it through the Holy Spirit who works within us. For us to gain by it, though, we have to consciously participate in the activity of God, in pursuing what Pope John Paul II called in section 41 of Veritatis Splendor a participated theonomy, since, in his words, “man's free obedience to God's law effectively implies that human reason and human will participate in God's wisdom and providence.” We are lost otherwise and fall into wrath and rebellion.

The short answer is that faith and reason cooperate with one another in our understanding who we are—our identity—which is most perfectly revealed by Christ himself who fully reveals mankind to himself. They are the two wings about which Christ spoke to St. Catherine of Siena as recorded by St. Raymond of Capua when he said, "You have two feet to walk and two wings to fly." With both these wings in flight, we are buoyed up by God's love.

Even so, we yet hit a limitation. As strong as we are created in the image and likeness of God whose natural law is written on our hearts, we need supernatural grace to perfect our natural gifts, and God provides it through the Holy Spirit who works within us. For us to gain by it, though, we have to consciously participate in the activity of God, in pursuing what Pope John Paul II called in section 41 of Veritatis Splendor a participated theonomy, since, in his words, “man's free obedience to God's law effectively implies that human reason and human will participate in God's wisdom and providence.” We are lost otherwise and fall into wrath and rebellion.

Dante Alighieri is also of great help here as he makes explicit in his Paradiso that there are things in the mind of God that the created being cannot know. Though our hope lies in our salvation, God’s mind is deeper than we can plumb, and that is a good thing because he shares of it with us is sufficient for our capacities. Dante writes in Canto XIX,

"In the eternal justice . . . The understanding granted to mankind is lost as the eye is within the sea: it can make out the bottom near the shore but not on the main deep; and still it is there, though at a depth your eye cannot explore." (lines 58-63)

While we have limits to what our science can do for us, we are not bereft of understanding. This understanding puts a new gloss on the relationship between faith and reason, between our faith and our science. We are at our best when we pursue our activities in full participation with the God who created us with the capacity to do so, who created us as creatures for our own sake, and who takes delight in us when we pursue our desire to understand the nature of created things with full awareness that there is a Creator whose mind has put all those things together. In the effort to advance a culture of life, after all, we must return to the work of understanding the relationship between our theology and our science. In doing so, we will find ourselves pursuing a new Golden Age.

"In the eternal justice . . . The understanding granted to mankind is lost as the eye is within the sea: it can make out the bottom near the shore but not on the main deep; and still it is there, though at a depth your eye cannot explore." (lines 58-63)

While we have limits to what our science can do for us, we are not bereft of understanding. This understanding puts a new gloss on the relationship between faith and reason, between our faith and our science. We are at our best when we pursue our activities in full participation with the God who created us with the capacity to do so, who created us as creatures for our own sake, and who takes delight in us when we pursue our desire to understand the nature of created things with full awareness that there is a Creator whose mind has put all those things together. In the effort to advance a culture of life, after all, we must return to the work of understanding the relationship between our theology and our science. In doing so, we will find ourselves pursuing a new Golden Age.

Footnotes:

1 Available at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/letters/1988/documents/hf_jpii_let_19880601_padre-coyne_en.html

2. Pope Benedict XVI, “Papal Address to Science Academy,” October 28, 2010, available at http://www.zenit.org/en/articles/papal-address-to-science-academy.

3 Ibid.

4 The length of this period is misleading, though. The next great scholastic effort made by the West after the death of Boethius did not occur until the twelfth century, the one that gave Averroes and all his great commentaries to the West.

5 For a full treatment of this, see Jonathan Lyons, House of Wisdom (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009). Other resources pertaining to this point include the following: Mirza Tahir Ahmad, "The Quran and Cosmology." Revelation, Rationality, Knowledge and Truth. (North Haledon, NJ: Islam International Publications, 1998). Available online at http://www.alislam.org/library/books/revelation/part_4_section_5.html; M. B. Altaie, "The Scientific Value of Dakik al-Kalam," Islamic Thought and Scientific Creativity. Vol. 5, No. 2 (1994): 7-18. Available online at http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ip/dakik.pdf; Douglas Cox, "The Cosmology of the Koran" (2010). Available online at http://www.sentex.net/~tcc/quran-cosmol.html; Jon McGinnis, "Arabic and Islamic Natural Philosophy and Natural Science." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Dec. 19, 2006). Available online September 1, 2011, at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/arabic-islamicnatural/.

6 A goal it accomplished in 1992 when the American Supreme Court adjudicated in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that “[a]t the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. (1992). Accessed August 14, 2011, http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgibin/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=505&invol=833

7 John Paul II. Fides et Ratio. September 14, 1998. Accessed August 14, 2011, at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_15101998_fides-etratio_en.html

8 Scott Hahn and Benjamin Wiker, Answering the New Atheism: Dismantling Dawkins' Case against God (Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road Publishing, 2008).

9 John Paul II. Evangelium Vitae. March 25, 1995. Accessed August 14, 2011, at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/encyclicals/documents/hf_jpii_enc_25031995_evangelium-vitae_en.html

10 To paraphrase C. S. Lewis, we are not “bodies,” we are “souls” that form bodies; that is, our souls are the form of our bodies. Mere Christianity (San Francisco: Harper, 1952), p. 129. This is also what Statius explains to Dante in Canto XXV of the Purgatorio---that the work of the soul is to form an operative body that can manifest itself materially within the material world. Dante Alighieri. (1308-1321). The Divine Comedy: The Inferno, The Purgatorio, and the Paradiso. Trans. by John Ciardi (1957). New York: New American Library.

1 Available at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/letters/1988/documents/hf_jpii_let_19880601_padre-coyne_en.html

2. Pope Benedict XVI, “Papal Address to Science Academy,” October 28, 2010, available at http://www.zenit.org/en/articles/papal-address-to-science-academy.

3 Ibid.

4 The length of this period is misleading, though. The next great scholastic effort made by the West after the death of Boethius did not occur until the twelfth century, the one that gave Averroes and all his great commentaries to the West.

5 For a full treatment of this, see Jonathan Lyons, House of Wisdom (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009). Other resources pertaining to this point include the following: Mirza Tahir Ahmad, "The Quran and Cosmology." Revelation, Rationality, Knowledge and Truth. (North Haledon, NJ: Islam International Publications, 1998). Available online at http://www.alislam.org/library/books/revelation/part_4_section_5.html; M. B. Altaie, "The Scientific Value of Dakik al-Kalam," Islamic Thought and Scientific Creativity. Vol. 5, No. 2 (1994): 7-18. Available online at http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ip/dakik.pdf; Douglas Cox, "The Cosmology of the Koran" (2010). Available online at http://www.sentex.net/~tcc/quran-cosmol.html; Jon McGinnis, "Arabic and Islamic Natural Philosophy and Natural Science." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Dec. 19, 2006). Available online September 1, 2011, at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/arabic-islamicnatural/.

6 A goal it accomplished in 1992 when the American Supreme Court adjudicated in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that “[a]t the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. (1992). Accessed August 14, 2011, http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgibin/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=505&invol=833

7 John Paul II. Fides et Ratio. September 14, 1998. Accessed August 14, 2011, at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_15101998_fides-etratio_en.html

8 Scott Hahn and Benjamin Wiker, Answering the New Atheism: Dismantling Dawkins' Case against God (Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road Publishing, 2008).

9 John Paul II. Evangelium Vitae. March 25, 1995. Accessed August 14, 2011, at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/encyclicals/documents/hf_jpii_enc_25031995_evangelium-vitae_en.html

10 To paraphrase C. S. Lewis, we are not “bodies,” we are “souls” that form bodies; that is, our souls are the form of our bodies. Mere Christianity (San Francisco: Harper, 1952), p. 129. This is also what Statius explains to Dante in Canto XXV of the Purgatorio---that the work of the soul is to form an operative body that can manifest itself materially within the material world. Dante Alighieri. (1308-1321). The Divine Comedy: The Inferno, The Purgatorio, and the Paradiso. Trans. by John Ciardi (1957). New York: New American Library.

For Personal Reflection and Group Sharing:

1. Briefly explain what is meant by the idea that the book of nature and the book of Scripture were both written by the same Author, and they will not be in conflict when properly read and interpreted.

2. The New Atheism relies a great deal on science as a means by which to disprove the existence of God, but how can it not do so legitimately?

3. Why must we cultivate an understanding of the relationship between ourselves and our Creator if we are to live the fullness of Truth?

Response of Sean Hurt:

A framework for refuting anyone, particularly atheists, who believe that only efficient and material causes are valid is to advance the understanding not only do we need to know that all four causes are necessary for a complete comprehension of a thing, but that we also need to know that agency, the efficient cause, is both a natural and a supernatural phenomenon.

When I was an atheist, I actually encountered arguments like this from Ronda. I can’t tell you how little they perturbed my perception of the world. Maybe arguments like these work on other atheists but not on me. In any case, Jesus gave a good model of how to deal with someone with a sort of concrete, materialist point of view. Remember when Nicodemus asks Jesus about being born again? He wants to understand it in a material, concrete way. He asks Jesus if we can reenter our mother’s womb! I’m always amazed at how Christians get pulled into arguments like this and try to explain things reasonably. Jesus does the opposite. He speaks even more enigmatically, but more profoundly —“Amen, amen I say to you, no one can enter the Kingdom of God without being born of water and spirit…” Now, those are wondrous, intriguing words. They are difficult to ignore, but from a “scientific” point-of-view utter nonsense. Jesus is trying to break Nicodemus concrete understanding of the world. He’s trying to draw him into thinking spiritually and symbolically.

To think that matter is “all that matters” is to limit ourselves significantly.

I used to be a materialist like this. I thought that truth was the most important thing, and so we must be very careful in discerning the truth. Naturally, science seemed like the most reliable, rigorous way of getting to that truth, and so I thought that I should only believe in what can be scientifically proven. In a certain sense I guess that’s right. If you mull over scientific literature with a critical eye, probably you’ll never profess an untrue belief. In the same strand, you’ll probably never believe in anything of any consequence either!

It’s easy to sit on a tower of reason and look down on a mire of revelation. It’s clean on the tower; reason is ours—in our control. But the world of faith is messy, because we must trust in God to believe it. From the tower, it’s also easy to bash faith with all its jumps in logic filled-in with little miracles. But if you stay on the tower, you may see the precious light that saves, but you can never follow it.

It actually increases our understanding of our own value as human persons to know that an infinite being, a necessary being, cared enough for finite, contingent beings such as us that he brought us into being in the first place and has reserved for us an eternal destiny in joyful communion with him if that is our choice.

As an atheist I attacked the Christian faith. It’s one thing to argue why a certain philosophy is incorrect, it’s quite another to prove a philosophy morally wrong. That was a thorn in my side. I had no doubt that God was bunk, but I couldn’t really show that believing in God was wrong. I relied on this flimsy claim. That faith promulgates disordered criteria for accepting truth. That’s hardly compelling. So, there was a conflict there. I was sure that religion was false, but it seemed to do so much good. Even as an atheist I envied the faithful for their simple conviction while I marveled at my own moral impotence. So, this burning question rose up in my heart at the time of conversion, “is it not good to believe in something that helps you be good, even if it seems incorrect?”

Think of what it means if you really believe in God. Every human being was willed to life by God. All these people sitting around you are special, precious pieces God’s creation—cherished by Him, loved by Jesus. Could I ever treat others as fully human without faith in this principle? And if faith in this principle is possible, don’t we have a duty to learn it?

We are at our best when we pursue our activities in full participation with the God who created us with the capacity to do so, who created us as creatures for our own sake, and who takes delight in us when we pursue our desire to understand the nature of created things with full awareness that there is a Creator whose mind has put all those things together. In the effort to advance a culture of life, after all, we must return to the work of understanding the relationship between our theology and our science. In doing so, we will find ourselves pursuing a new Golden Age.

I’m a scientist, so the author is talking about something I’m intimately involved in. I really agree with his conclusion, that we must develop the relationship between theology and science. However, I wish that we could add something here. How do we start this process? In all practicality, how can I inform my science with my faith and vice versa? What can I do concretely?

Response of Tommie Kim, a Korean Post Master’s student at Holy Apostles.

In order to understand what it means the idea that the book of nature and the book of Scripture are both written by the same author, we must acknowledge the fact that both visible and the invisible things are all created by God as we proclaim it in the Nicene Creed. Dr. Tom Sheahen mentions that science only has access to visible world and the visible world can occupy space and time. But the invisible part of the creation can only be accessed by human and this is something science cannot comprehend. Science and theism thus cannot conflict each other but help each other. Pope John Paul II provides clear understanding of this connection. “Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.”

The New Atheism relies great deal on science as a means by which to disprove the existence of God. But it cannot do so legitimately because they cannot comprehend the invisible and have no way of disproving the immeasurable. Neither can science. For Atheist, the name God exists only as label because they still refer to “God” they do not believe in. So in a certain sense, it is not the existence of God that Atheist do not believe in but rather God’s omnipotence that they neglect to believe in. Most often, this is because Atheists have no direct experience of God in their life. It is very difficult to convince anyone to a belief in God through logical means. It is only through direct experience of God that faith can be obtained. However, what I perceive as the one of the cause to affirm people into Atheism is the Christians themselves. For Atheist who does not believe in the power of God’s omnipotence and the Holy Spirit, perceive God through Christians they encounter. We must be aware that our lives are not building higher wall between God and Atheist. I recall saying why the world is deteriorating with so many Catholics when the sea is salted with only 4% of salt in it.

We live in an age of ever abundance source of intellectual sources and highly advance technology. The level of technological advancement exceeded our expectation and we all wonder what the next progress will lead us into. Because science and technology achieved what thought was impossible, there is a tendency that this is affecting human moral. We realize the need of the science and technology but at the same time must bare I mind that almighty science (scientism) can never replace almighty God. Our lives will be at risk if we do not realize this limit. “We are at best when our activities are in full participation with the God who created us with the capacity to do so, who created us as creatures for our own stake, and who takes delight in us when we pursue our desire to understand the nature of created things with full awareness that there is a Creator whose mind has put all those things together.” As we are now entering the new Golden Age of advanced technology, it is necessary that we build our understanding on relationship between theology and science, between faith and reason. Otherwise, science will reach the dark end where destruction of human dignity, faith and truth awaits. In the field of scientific research, a positivistic mentality took hold which not only abandoned the Christian vision of the world, but more especially rejected every appeal to a metaphysical or moral vision. It follows that certain scientists, lacking any ethical point of reference, are in danger of putting at the centre of their concerns something other than the human person and the entirety of the person's life. Further still, some of these, sensing the opportunities of technological progress, seem to succumb not only to a market-based logic, but also to the temptation of a quasi-divine power over nature and even over the human being.

Response of Kathleen Brouillette, a student at Holy Apostles.

What is it about the Church that makes so much of society try to discredit Her? Scientists with their “proofs,” atheists with their doubts, media with their sensational headlines and half-truths – all attack the Church. Interestingly, the Church seeks to work together with all of them for the betterment of mankind, and to bring us all closer to the Truth.

Holy Mother Church knows, in Her wisdom, that together the book of nature and the book of Scripture tell the complete story of creation, and of mankind’s place in it. She knows that man is body and spirit, shaping his life in the cosmos designed by the Creator, and that all things work together for our good to accomplish the will of God. We cannot obtain a clear picture of that unless we understand the origin and end of body and soul, the cosmos and man, the visible and invisible.

In the relationship between faith and science, the Church leads the way, and yet is accused of being archaic and irrelevant. Last week, for example, there was a story about pluripotent stem cells being created from one’s own adult stem cells, and “programmed” to become whatever type of cell is necessary to bring about healing. I learned about pluripotent cells at least six years ago in a science class here at HACS. At the same time, the media was full of anti-Catholic stories about the necessity of embryonic stem cells because of the death of Christopher Reeve, and the efforts of Michael J. Fox to find a cure for his own Parkinson’s Disease. Years of negative press and sensationalized, selective half-truths claimed that the Church is against stem cell research because of Her stand against embryonic stem cell use. She has, however, been very much in the forefront of adult stem cell research - gathering scientists and funding their work. Most of the success with stem cells has come, NOT from embryonic stem cells anyway, but from adult stem cells. That truth has gotten little press, perhaps because the position of the Church can’t be criticized.

A real synthesis between faith and reason can only come about, in my opinion, when the brilliant minds at work in the Church speak out; when the Church demonstrates and makes known that She is at the forefront of progress, supporting research, science, psychology etc. in their proper perspective. How many people know Catholic priest Gregor Mendel pioneered the field of genetics, or Catholic priest Georges LeMaitre first presented the theory that the cosmos is expanding (originally dismissed and then supported by no less than Albert Einstein)?

Being at Holy Apostles, I have read many Papal documents and have been exposed to the true position of the Church on scientific progress. I would never have known about them had I not been here. There is no mention of them from the pulpit. The average man in the pew is not even aware they exist, let alone how to access them. Here, again, is an area where formation of the clergy and the people is critical. I believe that it is truly essential for the Church to do a better job of getting her entire message out there!

Agnostic scientist and author Robert Jastrow admits, in God and the Astronomers, “For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance, he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.”

1. Briefly explain what is meant by the idea that the book of nature and the book of Scripture were both written by the same Author, and they will not be in conflict when properly read and interpreted.

2. The New Atheism relies a great deal on science as a means by which to disprove the existence of God, but how can it not do so legitimately?

3. Why must we cultivate an understanding of the relationship between ourselves and our Creator if we are to live the fullness of Truth?

Response of Sean Hurt:

A framework for refuting anyone, particularly atheists, who believe that only efficient and material causes are valid is to advance the understanding not only do we need to know that all four causes are necessary for a complete comprehension of a thing, but that we also need to know that agency, the efficient cause, is both a natural and a supernatural phenomenon.

When I was an atheist, I actually encountered arguments like this from Ronda. I can’t tell you how little they perturbed my perception of the world. Maybe arguments like these work on other atheists but not on me. In any case, Jesus gave a good model of how to deal with someone with a sort of concrete, materialist point of view. Remember when Nicodemus asks Jesus about being born again? He wants to understand it in a material, concrete way. He asks Jesus if we can reenter our mother’s womb! I’m always amazed at how Christians get pulled into arguments like this and try to explain things reasonably. Jesus does the opposite. He speaks even more enigmatically, but more profoundly —“Amen, amen I say to you, no one can enter the Kingdom of God without being born of water and spirit…” Now, those are wondrous, intriguing words. They are difficult to ignore, but from a “scientific” point-of-view utter nonsense. Jesus is trying to break Nicodemus concrete understanding of the world. He’s trying to draw him into thinking spiritually and symbolically.

To think that matter is “all that matters” is to limit ourselves significantly.

I used to be a materialist like this. I thought that truth was the most important thing, and so we must be very careful in discerning the truth. Naturally, science seemed like the most reliable, rigorous way of getting to that truth, and so I thought that I should only believe in what can be scientifically proven. In a certain sense I guess that’s right. If you mull over scientific literature with a critical eye, probably you’ll never profess an untrue belief. In the same strand, you’ll probably never believe in anything of any consequence either!

It’s easy to sit on a tower of reason and look down on a mire of revelation. It’s clean on the tower; reason is ours—in our control. But the world of faith is messy, because we must trust in God to believe it. From the tower, it’s also easy to bash faith with all its jumps in logic filled-in with little miracles. But if you stay on the tower, you may see the precious light that saves, but you can never follow it.

It actually increases our understanding of our own value as human persons to know that an infinite being, a necessary being, cared enough for finite, contingent beings such as us that he brought us into being in the first place and has reserved for us an eternal destiny in joyful communion with him if that is our choice.

As an atheist I attacked the Christian faith. It’s one thing to argue why a certain philosophy is incorrect, it’s quite another to prove a philosophy morally wrong. That was a thorn in my side. I had no doubt that God was bunk, but I couldn’t really show that believing in God was wrong. I relied on this flimsy claim. That faith promulgates disordered criteria for accepting truth. That’s hardly compelling. So, there was a conflict there. I was sure that religion was false, but it seemed to do so much good. Even as an atheist I envied the faithful for their simple conviction while I marveled at my own moral impotence. So, this burning question rose up in my heart at the time of conversion, “is it not good to believe in something that helps you be good, even if it seems incorrect?”

Think of what it means if you really believe in God. Every human being was willed to life by God. All these people sitting around you are special, precious pieces God’s creation—cherished by Him, loved by Jesus. Could I ever treat others as fully human without faith in this principle? And if faith in this principle is possible, don’t we have a duty to learn it?

We are at our best when we pursue our activities in full participation with the God who created us with the capacity to do so, who created us as creatures for our own sake, and who takes delight in us when we pursue our desire to understand the nature of created things with full awareness that there is a Creator whose mind has put all those things together. In the effort to advance a culture of life, after all, we must return to the work of understanding the relationship between our theology and our science. In doing so, we will find ourselves pursuing a new Golden Age.

I’m a scientist, so the author is talking about something I’m intimately involved in. I really agree with his conclusion, that we must develop the relationship between theology and science. However, I wish that we could add something here. How do we start this process? In all practicality, how can I inform my science with my faith and vice versa? What can I do concretely?

Response of Tommie Kim, a Korean Post Master’s student at Holy Apostles.

In order to understand what it means the idea that the book of nature and the book of Scripture are both written by the same author, we must acknowledge the fact that both visible and the invisible things are all created by God as we proclaim it in the Nicene Creed. Dr. Tom Sheahen mentions that science only has access to visible world and the visible world can occupy space and time. But the invisible part of the creation can only be accessed by human and this is something science cannot comprehend. Science and theism thus cannot conflict each other but help each other. Pope John Paul II provides clear understanding of this connection. “Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.”

The New Atheism relies great deal on science as a means by which to disprove the existence of God. But it cannot do so legitimately because they cannot comprehend the invisible and have no way of disproving the immeasurable. Neither can science. For Atheist, the name God exists only as label because they still refer to “God” they do not believe in. So in a certain sense, it is not the existence of God that Atheist do not believe in but rather God’s omnipotence that they neglect to believe in. Most often, this is because Atheists have no direct experience of God in their life. It is very difficult to convince anyone to a belief in God through logical means. It is only through direct experience of God that faith can be obtained. However, what I perceive as the one of the cause to affirm people into Atheism is the Christians themselves. For Atheist who does not believe in the power of God’s omnipotence and the Holy Spirit, perceive God through Christians they encounter. We must be aware that our lives are not building higher wall between God and Atheist. I recall saying why the world is deteriorating with so many Catholics when the sea is salted with only 4% of salt in it.

We live in an age of ever abundance source of intellectual sources and highly advance technology. The level of technological advancement exceeded our expectation and we all wonder what the next progress will lead us into. Because science and technology achieved what thought was impossible, there is a tendency that this is affecting human moral. We realize the need of the science and technology but at the same time must bare I mind that almighty science (scientism) can never replace almighty God. Our lives will be at risk if we do not realize this limit. “We are at best when our activities are in full participation with the God who created us with the capacity to do so, who created us as creatures for our own stake, and who takes delight in us when we pursue our desire to understand the nature of created things with full awareness that there is a Creator whose mind has put all those things together.” As we are now entering the new Golden Age of advanced technology, it is necessary that we build our understanding on relationship between theology and science, between faith and reason. Otherwise, science will reach the dark end where destruction of human dignity, faith and truth awaits. In the field of scientific research, a positivistic mentality took hold which not only abandoned the Christian vision of the world, but more especially rejected every appeal to a metaphysical or moral vision. It follows that certain scientists, lacking any ethical point of reference, are in danger of putting at the centre of their concerns something other than the human person and the entirety of the person's life. Further still, some of these, sensing the opportunities of technological progress, seem to succumb not only to a market-based logic, but also to the temptation of a quasi-divine power over nature and even over the human being.

Response of Kathleen Brouillette, a student at Holy Apostles.

What is it about the Church that makes so much of society try to discredit Her? Scientists with their “proofs,” atheists with their doubts, media with their sensational headlines and half-truths – all attack the Church. Interestingly, the Church seeks to work together with all of them for the betterment of mankind, and to bring us all closer to the Truth.