by

Bryan Mercier

Some individuals have a difficult time connecting with God in prayer. Others find it difficult to keep a steady prayer life. Still others possess a solid spirituality but seek to go deeper. Later in this chapter, we will discuss how to pray along with the different prayer practices the Catholic Church offers. However, in keeping with the theme of this book, it is first necessary to discuss the different polarizations and condemnations regarding prayer that stem from different groups within the Church.

Clearly, these extremes, these polarizations are untrue, and the false judgments need to end. It is important not to condemn what the Church herself does not condemn. This is the sort of immature spirituality that must be left behind. Unity and understanding must be cultivated instead. Just because you personally don’t not like the Latin Mass (or Praise and Worship music), does not mean that they are wrong or false. The truth is that neither traditional prayer, nor charismatic prayer, is wrong. Both are Catholic! Both are authentic expressions of worship, and both are approved by the Church. Both have an ancient tradition. Both have their strengths and weaknesses, and both are needed. Moreover, both sides could learn something from the other, even if they still prefer their own style.

It all started by going to the more charismatic evening Mass. (The traditional Mass was too early in the morning for me). At the beginning, I failed to understand this style of worship. Before God changed my views, I griped about how everyone was fake or just trying to put on a show. Apparently, I had an uncanny gift to read each and every person’s heart. These were typically ignorant thoughts from someone who did not understand something outside his own narrow worldview. Eventually, I would realize that the celebration of this Mass was very reverent. The people loved God with all their hearts and gave everything they had to Him.

A key lesson God has taught me again and again in the spiritual life is that when I am open, (truly open and not merely open when I’m comfortable), my life will be changed. Astonishingly, the FOPs visibly filled with the Holy Spirit, and they bore good fruit. They were incredibly prayerful, reverent, vibrant, and powerful, and many times life changing. To my surprise, most of my major spiritual breakthroughs and deep healings occurred at these FOPs.

I should note too that some rather large healings and deep spiritual encounters with God also took place at Eucharistic Healing Masses, Eucharistic FOPS, and at Sunday Masses, all of which were extraordinarily powerful experiences. Once I learned to truly open myself up to the Holy Spirit (something many Catholics have an extremely difficult time doing), then God could work in ways I didn’t consider possible. Even though charismatic prayer and worship can have the tendency to rely too heavily on feelings, when done properly, it has an amazing ability to transform a person and open them wholly to God.

It has been 15 years since those days, and I still have a fire burning in my heart for the Lord Jesus. Thanks be to God! God taught me very important lessons about not putting the Him in a box and about opening myself up to His Spirit in different ways. So, am I charismatic or traditional? The answer is that I'm Catholic. A Catholic who is both.

Sometimes I pray lifting my hands high in the air to praise the God of the universe with all my being. At other times, I sit or prostrate myself in front of His Majesty saying little or nothing – just aware of His awesome presence in and around me. Sometimes I praise God through music and audible or inaudible praise. At other times, my prayer is just to “Be still and know that I am God.”

Needless to say, I have adequate exposure to many styles and forms of worship within our wonderful Church. I see the power and beauty of it all. In all of these cases, I seek to cultivate a deeper contemplative life, a deeper relationship with Love Himself.

Charismatic Protestant are able to join certain denominations. More traditional Protestants must find other denominations. Unlike Protestantism, the Catholic Church is not an either/or Church. It's a both/and Church. Thank God! The great thing about the Catholic Church is that there are many different ways to pray and serve God. There are Franciscans and Carthusians, Dominicans and Trapists, charismatic minded Catholics and traditionally minded Catholics. None of these are wrong or false, just different. Moreover, a person should not be judged as wrong or inferior because they pray differently than what you prefer. Even if there are some abuses in the Church, in some areas more than others, gossiping, complaining, judging, labeling, and compartmentalizing are not helpful. This is a sure sign of spiritual immaturity. The Lord Jesus calls us to compassion, to love, and to humble evangelization.

Over the years, I have learned the majesty and mystery of the traditional Mass and traditional forms of prayer, which can lead you to contemplation and a deep spiritual life. I have also witnessed the power, joy, and self-donation of Praise and Worship, which when done correctly, can also lead to contemplation and a deep, loving relationship with God.

Some of the super traditional students at my old college ended up becoming charismatic by the end of their tenure, and some of the charismatic students become traditional in their worship and practice. Most people switch sides, or more accurately, open themselves up to both. They are rightly open to how the Holy Spirit desires them to pray. They do not fight Him, close their hearts to Him, or say silly things like, “Oh, that’s just not me, I could never pray that way.”

While the students at my alma mater might prefer to focus more on one or the other (traditional or charismatic), most of the students see the beauty in the other, and they possess a healthy respect for it, and that is how it should be! People who limit the Holy Spirit stunt themselves. We must seek to understand other styles of prayer in the Church and have a respect for them. If we are against even trying a style of prayer that makes us uncomfortable, then we are not fully open to the Holy Spirit and must pray about that.

Whole books have been written on the topic of how to pray and how to grow in the spiritual life. Therefore, the main focus of this chapter will be to highlight the different styles of Catholic prayer.

At the simplest level, prayer is a relationship with God who desires more than anything to have a relationship with us. Prayer is speaking to God and listening; it is setting our hearts on Him and thinking about Him, and it is seeking to do what pleases Him in everyday circumstances. Saints like St. Teresa of Avila, St. Francis De Sales, St. John of the Cross, and others all teach us that there are distinct stages of prayer. The path begins simply with heartfelt vocal prayer and then proceeds to deeper mental prayer and meditation. Eventually, infused prayer and contemplation follow, which culminate in a transforming union with God.

In his book, Jesus of Nazareth, Benedict XVI sums up what prayer is in a nutshell; “That is what prayer really is – being in silent inward communion with God. … Praying actualizes and deepens our communion with God. Our praying can and should arise above all from our heart, from our needs, our hopes, our joys, our sufferings, from our shame over sin, and from our gratitude for the good. It can and should be a wholly personal prayer.” Let's explore what this all means practically.

Drawing from the wisdom of the saints and prayer masters, here are just a few suggestions to help enter into vocal prayer and into deeper states of the spiritual life. As Benedict XVI just correctly stated, one of the most important principles is to pray from our hearts, not just your heads. A person cannot merely rattled off words routinely into the void or to a vague notion of God. This is not true prayer and will not help advance you closer to our Lord. Pope Benedict XVI states the same; “The other false form of prayer the Lord warns us against is the chatter, the verbiage, that smothers the spirit. We are all familiar with the danger of reciting habitual formulas while our mind is somewhere else entirely.” Ultimately, prayer should proceed from our love of God. Prayer must done out of love, rather than because of fear, guilt, or mere routine. It’s the difference between really desiring to spend time with your boyfriend/girlfriend or doing so merely out of obligation.

Vocal prayer is communication with God. However, before we even begin speaking to Him, it is imperative that we take time to quiet our inner-self and to place ourselves in the presence of God. Take 30 seconds or so for this task – to focus on God’s presence within you or around you. Be still and be aware of His presence. When we are aware of God and His presence there listening to us, we will pray with more focus. Additionally, when we address God, we must speak to Him personally, as someone close, not far away. The more personal one makes prayer, the more fruitful it will be.

Then, when finally addressing God, speak slowly and speak from the heart. We must focus on every word we are praying while continuing to focus on His presence. Below are some examples of ways to pray using vocal prayer:

Asking God for the things you need in life, both temporal and spiritual. Some people only pray for others, never for themselves. This is a mistake. We must always ask our Father for the things we need.

Interceding or praying for others. We can pray for people in need or for people doing well. The Bible clearly teaches that praying for others; family, friends, relatives, people you have and will evangelize to, and even people in positions of authority is a good thing (1 Tim. 2:1-4).

Chant/Polyphony: On the other side of the coin, Chant and polyphony music, used mostly in more traditional worship, also cultivates the mind, heart and soul. It draws the whole being of a person up into the presence of the Lord, and allows that soul to be aware of the transcending greatness, awe, and majesty of God. It fosters a deep awareness of God and His Holy presence, and it can lead people to deeply meditate on and contemplate His divine Majesty.

Thanking God for everything He has given us: life, health, family, friends, talents, grace, love, forgiveness, our gifts and talents, and so much more. Thanksgiving to God should flow freely and often from our hearts.

The Divine Mercy Chaplet: The great prayer of mercy where a person meditates on the passion of Jesus while beseeching His mercy for themselves and for the whole world.

Mental prayer, also known as quiet prayer or prayer of the heart, is indispensable for the spiritual life. While vocal prayer is indispensable, mental prayer is far more important and efficacious. As Catholics, it is essential for us to take time to quiet our hearts and our minds, to quiet ourselves from the business of our daily grind, and to just let ourselves be in the presence of God. This silent prayer is where we find His Majesty, and where divine intimacy takes place.

St. Theresa of Avila taught that virtue grows incomparably more in quiet prayer verses vocal. In fact, every saint agrees unanimously that those who don’t meditate or take quiet time with God will remain spiritually stunted. Some priests have even grown cold through their lack of prayer, especially mental prayer. Not only do they suffer from it, but their parishes to do. You can’t give what you don’t have. St. Padre Pio states that the failure to meditate can be likened to a person who gets dressed every day and then never looks in a mirror. Therefore, they do not know if they is dirty or not.

Unfortunately, it is common to speak to God but not to listen, and this it is equally common to know of God but never really come to actually know Him. There is a big difference between knowing about, and actually knowing. It is imperative to unplug from our ipods, computers, phones, and other technology from time to time. We need to daily cultivate some silence in our lives. The more we can be at peace in the quiet, the more we will be disposed to meditate, to listen, and to be aware of the indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit. Below are some examples of ways we can pray using mental prayer:

Thinking and reflecting on God. Taking quiet time (in church, our bedroom, etc) to think about God, who He is, His plan for our life, His great love for us, or anything else, is a form of prayer. (See more on “Meditation” below).

Doing God’s will. Fr. Thomas Dubay, a 21st century prayer master, teaches us that doing God’s will daily is a form of prayer. Along with our routine prayers, we should be reflecting on what God desires from us in life and in general. According to St. Teresa of Avila and other mystics, the more we follow God’s will obediently, and the more we rid ourselves of sin (especially and necessarily mortal sin), the more God will draw us closer to Himself, infuse His life within us and commune with us.

Prayer times usually consist of asking God for something, or praying for some need, etc. Whether it is a good or a “bad” prayer time, edifying or dry, fulfilling or a “waste of time,” it is important to practice this faithful obedience to God, learning to be content in His presence, as a servant would be attentive in the presence of his king. This is required for anyone seeking to grow in a deep and abiding relationship with God.

Reading the Bible or a Spiritual Book: Reading Scripture, the lives of the saints, or a spiritual classic is a perfect way to learn and meditate on our faith, to ponder what we need to change or grow in, and to consider how to live more wholeheartedly for the Lord Jesus.

Meditation helps us to grow closer to God spiritually, to grow in virtue and in holiness.

The Pocket Catholic Dictionary offers a good definition of meditation. “Meditation: Reflective prayer. It is that form of mental prayer in which the mind, in God’s presence, thinks about God and divine things. … The objects of meditation are mainly three; mysteries of faith, a person’s better knowledge of what God wants him or her to do, and the divine will, to know how God wants to be served by the one who is meditating.”

Meditation is where we take time to think about God and the mysteries of our faith. We could ponder the life of Jesus, His death, or His resurrection. We could also ponder our lives, what God desires from us, how we can follow Him more faithfully, what faults we need to work on and how we can do that. We can also consider God’s surpassing greatness, His unconditional love for us, and how He demonstrates that love by dying on the cross for us. We could also meditate on are our final days, our deathbed, heaven, hell, eternity, and much, much more. In time, and with daily dedication, meditation will bear much fruit in our spiritual lives, leading to infused prayer, transformed lives, and union with God, which should be the goal for each and every one of us.

Pope John Paull II reminds us that, “Jesus urges us to ‘pray without becoming weary.’ Christians know that for them prayer is as essential as breathing … Prayer is not simply one occupation among many, but it is at the center of our life with Christ.” This sums up our prayer journey in a nutshell; namely, that prayer should not be something we try to squeeze in our day, but it should be our very life, our breath, a large part of our being. That is why St. Paul exhorts is us to, “Rejoice always, pray constantly, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.”

Hardon, John A, Pocket Catholic Dictionary, New York. DoubleDay, 1985.

Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, New York. DoubleDay, 2007.

Pope John Paul II, Go in peace, Chicago, IL. Loyola Press, 2003.

Questions for Reflection:

• What are some of the polarizations in the Church that some Catholics fall into?

• Have you ever found yourself judging or condemning a style of worship, which the Church permits, that is different than yours? If so, why?

• If you do not like the Latin Mass, would you be open to trying it? Or, at least, do you understand the beauty of that worship, and will seek to possess a deep respect for it? Why or why not?

• If you would not normally use more expressive prayer, like putting your hands in the air or praising God openly, would you be open to it? Or, would you at least be open to understanding the meaning of it all and gaining a healthy respect for it? Why or why not?

• Discuss the pride and self-righteousness that may come with wagging fingers at people who worship differently than you do?

• What styles of prayer do you use? Would you be open to trying ones you are not familiar with? Why or why not?

• Knowing that prayer is our life, what are the obstacles that you face (or will find yourself facing), and how can you overcome them?

Do you seek to foster a deep contemplative relationship with God, or is your prayer life more on the surface? Explain.

• Do you read books on prayer to help you grow?

Response from David Tate:

In every society, there are social guidelines. I appreciated Mercier’s comment about people feeling their “method of worship is correct or superior”. I felt like there is something beneath the surface of criticism. Many times guidelines support specific themes. These themes might include bodily exposure, gender, social status, linguistic styles, respect for the community, or respect for the individual. One guideline that seems to have been a part of my culture was the idea of not drawing undue attention to yourself. In light of this, I feel I am quick to notice when people are making a spectacle of themselves. One interesting story I recall involves feet. I have seen my share of shod feet, sandaled feet, and bare feet. I do not find “naked” feet shameful, providing that they are following some communal custom. I recall seeing a person once (actually twice) who was not wearing anything on their feet. The circumstances at the time really made me feel like they were making a spectacle of themselves. In like manner, I feel my personal feelings about worship come from the same mold. If there is a style of prayer where people are raising their arms or speaking out loud, I am comfortable with that. What I don’t like is when people, ignoring social cues, practice a worship style that draws attention to themselves. It is possible that I am hitting a common experience with others, in this opinion.

I strongly feel that styles of worship are guided by social ‘pressures’ and spiritual hungers. Perhaps because of our lack of a set family profile of religion, the Latin Mass was never anything to be criticized; especially since we didn’t have any practical connection with the Catholic Church (i.e. relatives, etc.) I, even though it is exactly opposite of my upbringing, have found it very easy to be in a Charismatic atmosphere when I was craving it. I think that when we allow too much to be controlled by our social surroundings, we are then in need to look at our spiritual lives for signs of stagnancy. There is the immature habit of criticizing others for being different. However, if we have not seen changes in our own spiritual condition, then maybe we need to look more closely at other people’s differences. There are multiple styles of prayer and worship, each one having its specific benefits.

I have for a long time desired to teach “Forms of Prayer”. I remember seeing a program on TV that discussed a style of therapy for certain mental disorders. What they did was to physically act out the most fundamental movements that we progress through from the time of our birth. Things as simple as lying on our back, waving our arms and legs in the air, practicing making ‘baby style’ noises. These actions were followed by the motions of sitting on the floor with your legs out, crawling on all fours, etc. I have believed that styles of prayer follow a similar training. Actions that our bodies don’t know how to perform cannot be called upon by our mind. There is probably a bunch of psychological explanation to this thinking, but I still prefer a simplistic understanding.

I think that we underestimate the power of the common vices when it comes to “problems”. We love to rationalize away our judgments of others, but it still doesn’t say why we are lacking in our obligation to love others, and to see Christ in them. Just like a parent sees their infant as a baby. We, too, should see others as moving through chapters of growth. It is quite easy to be guilty of vices like envy or coveting or jealousy when we are running down others. Don’t we go through life having the proverbial three fingers pointing back at us when we are pointing at others?

In brief, I grew up hearing on rare occasion people praying and speaking to God as if He was right there with us. Most of these times, it was during times of thanksgiving. When I was in high school, I went to many positive ‘study-style’ Bible studies. During my college days, I experienced quite a few Charismatic services. I have had experiences that could not have been labeled by any other terms than to say they were directly caused by the presence of the Holy Spirit. Being now a seminarian, I find that my life experiences give me a much closer ‘feather-touch’ regarding the wisdom for things that are individual versus things that are communal. Sometimes I have daydreamed that if I had already a family-given style of prayer, would I have had to go through a time of rebellion like those that were given “religion” as a kid?

I view my desires and my obstacles to be closely related. I have been learning more and more about the contemplative history of the Church over the last fifteen years. I see that the act of choosing how we spend the day, or even the next hour, has a lot to do with developing our habits. Am I developing my habits of work more than prayer? Individual concerns more than communal? Personal gratification over self-denial? Even the act of deciding about the morning cup of coffee involved great personal issues. I once read that God inhabits not only the praises of His people, but the prayers of His people as well. I whole heartedly agree with Mercier saying “Meditation helps us to grow closer to God”. How often do I really allow others to make decisions for me? I hope to grow in a truer meaning of contemplation that includes my own personal characteristics. Finding out the meaning of contemplation and what my personal characteristics are – this is the life-long challenge.

Response from Tommie Kim:

It is not until very recently that the Holy Spirit Seminar has been introduced to Korea. I was a university student when I first learned about Holy Spirit Seminar events. My first experience of such charismatic prayer was simply shocking. I grew up with devout Catholic parents. I served as altar boy, and that led me to be accustomed to solemn and quiet Masses. My first perception of the seminar reminded me of some kind of Protestant activity or act of secularization. In simple terms, it was a religious shock for me.

As the week passed by, I started looking at the event from a different perspective. God is with us at all times. Likewise, God works in each and every one of us in a very different way. However, I had limited understanding of faith at that time, sort of trapped in my own world so I was not able to accept and perceive the fact that the Holy Spirit could work in such a different way. Since then, friends and people around me recommended that I to join the seminar. Although unwilling and reluctant, I do admit witnessing special experiences through others. I witnessed a man screaming out of horror against dark forces surrounding him. He ran to grab the priest for help. After receiving sacrament of reconciliation after a life-long distance from that sacrament, he was freed from darkness. I was amazed to see the change that could take place in a man. I perceived the experience as the grace of God. Such gift of the Holy Spirit not only helps one but all who surround and share the experience.

In Korea especially in the many cities, all parishes have charismatic prayer groups who offers charismatic Masses and/or overnight prayers. Sometimes, it requires consistent care and guidance of the priests and sisters of parish in order for the group to grow stronger in faith. However, some other times, it requires a little more freedom and independence of the group to sustain and grow by itself, instead of excessive interference from priests and sisters. As a worst example, sometimes speakers at the seminar face censor from priests in the form of asking them to provide the speaker’s talk prior to the speech.

The Catholic church in Korea is truly and exceedingly centered on priests and religious. So, it is crucially important that they show a good exemplary model of prayer life. However, priests rarely pray in these days so it becomes difficult to teach proper prayer life to the lay believers. Simply put, externally, we see church growing in numbers and external social activity seems very active. However, there are not enough priests who can lead them to a deeper prayer life. Moreover, we are seeing priests who enjoy life even more than the lay believers, some of them even leading the parish into conflicts and division. Priests with radical leftist ideology add to this disappointment that is leading the believers to leave the church.

Response from Sean Hurt: (Note from Dr. Ronda: At first this response seems too general, and not so related to the chapter, but it really is since it provides a metaphor for all our ways of judging, including judging the way others pray.)

Unfortunately, there are always people within the Church who believe that their method of worship is correct or superior…

I’m embarrassed to say this now, looking back, that I entered Peace Corps with the quintessential Peace Corps fantasy. The fantasy goes something like this: I’m going to come to this developing country full of humble people. They will see my modern farming techniques and be amazed. Being rational people, motivated by material interest, they will immediately change their life-long habits and conform to modern, developed ways. Unfortunately, I didn’t know the scripture that says, “No one who has been drinking old-wine desires the new, for he says, ‘The old is good.’”

Now, that’s a fantasy. What really happens when you get your boots on the ground? You show these humble people your “developed-world” techniques and receptions range from apathy, amusement, concern (for my mental health) to outright anger! In fact, I’ll tell you what happens. They start thinking it’s I who needs help! They don’t like the way I hang my laundry or how I scramble my eggs! They think, “this fool, he doesn’t know how to do anything right!” After this happens a hundred times, you start to get very frustrated. You think, “These people! They are such closed-minded, sticks-in-the-mud. They don’t try anything new, even though it’s better. It’s their own fault they’re so backwards. They think they’re right about everything—even down to the minutest detail.”

A lot of people leave Peace Corps with that attitude, and then they return home and realize that their attitudes about Americans have changed. “Americans are so private and unfriendly! They spend so much money on stupid stuff! All they value is work and money!” Just as I judged the Malawians harshly, I started treating American in the same way. Malawi left an indelible mark on my values and beliefs, and when Americans did not see the light I chastised them, “Americans are so closed-minded. They’re stuck in their way; they can’t change etc.” It’s so easy to think that your way is the one right and holy way.

There are lots of lessons to be learned from this example. I hope you can see that our fallen nature tends to inflate the importance of minor details in our own culture. In Malawi, they had ideas about the right way to crack an egg. If you didn’t do it that way, you were just wrong. If you think Americans don’t do this—think again; we’re just as bad. Now, I’m not advocating some kind of cultural relativism, not at all. Some practices are unacceptable, and battles need to be fought. However, hair-splitting is divisive; it harms human solidarity, and among Christians it destroys unity.

Consider another lesson. In Malawi, obviously, I was an outsider. As a pariah, I felt vulnerable and weak. That, in turn, led me to defensive thoughts which led to judgment that ended in hate. So, when we’re in the midst—surrounded by another culture, we have to be on guard. Not guarded from the strangers, but from our own proclivity towards rash judgment.

I think recognizing that we’re in another culture is harder than we think. As I mentioned before, I go to two different parishes. One is more traditional, another contemporary. Honestly, I often feel uncomfortable at the traditional parish. The parishioners are more conservative. They dress a certain way, and look a certain way. They have their own culture and I stick out with my long hair and shaggy beard. But if there’s going to be Catholic unity it will take communication and interaction across divisions. This means putting yourself in situations in which you feel vulnerable, uncomfortable and, often times, judged. Likewise, it means we must take special care to make strangers feel welcome in our Christian community—no matter how strange they seem.

Response of Fr. Dominic: (Note from Dr. Ronda: Fr. Dominic is the author of the chapter in this book The Priest in Community and taught the first class based on this book with me in Spring of 2014. During the class, when Bryan Mercier came to dialogue with us, Fr. Dominic took exception to Mercier’s rejection of centering prayer. It became clear that the kind of centering prayer Fr. Dominic teaches, based on early versions of this prayer, was different from the type of centering prayer now often being taught which is critiqued by Mercier. I asked Fr. Dominic to describe to us how he teaches it.)

Concerning Christian centering prayer it is based on focusing on God by consciously disconnecting from other thoughts. You close your eyes to the surrounding distractions and stop the interior dialogue, the emotions that come with the people you know, and sensory experiences. Nothing is worth thinking about at this time of centering prayer, not even the thought about yourself. This is because How you are “now” is the way you are going to be in the future. The way you see anything is the way you see everything. The way you do anything is the way you do everything.

In doing centering prayer, you simply need to be in the presence of God, not being loaded down with the past. There are many biblical images for centering prayer: Sabbath rest is where you are to get out of the achieving mode, or thinking about who likes you or who doesn’t. Rest is above time. It is eternity in the present moment. It is being in the inner room of Matthew 6.6, where I am forgiven of all and in all.

(During the class a question was asked as to whether this means that Catholic centering prayer substitutes the feeling of being forgiven for sacramental confession. Fr. Dominic explained that it is a good preparation for the sacramental confession. Centering prayer helps to guide against having the sacramental confession as mere ritual, that is, frequenting the sacrament of confession without sincere repentance for ones sins and thereby “being caved into oneself” which is the real meaning of sin as St. Augustine defined it. With the aid of centering prayer, the penitent after the sacramental confession will have no doubt that God, who is eternity in the now, has forgiven and forgotten ones sins and therefore, there will be no need of bemoaning and rehearsing the sins over and over again. Centering prayer helps in evacuating the emotional junk of a life time.)

The passive dimension of centering prayer is where one collapses in the presence of God to be refreshed. It is allowing God to be in charge and not you. This is the real meaning of the primacy of grace in the Christian spirituality. Therefore, the active dimension of centering prayer is cooperating with this grace.

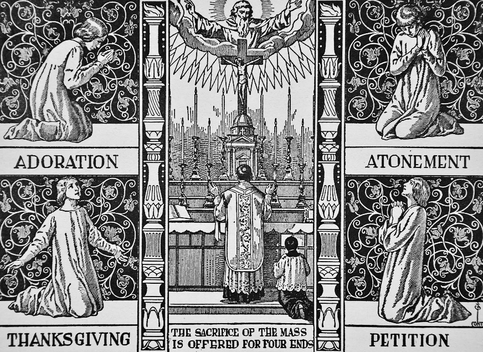

The great Catholic tradition speaks of the four basic forms of prayer; adoration, petition, intercessory and contemplation. Centering prayer is closely connected to adoration. When we adore, we open the little ego to the mystery of God. We acknowledge the godliness of god and that our life is not about us. etymologically, adoration is from the Latin words “ad” and “ora” - meaning to the mouth of. To adore is to be turned with your whole life towards God so that you are mouth to mouth-face to face with God. Hence, we breathe in the divine grace. God’s glory is not intensified by our adoration rather we become rightly ordered by our adoration, it is ordering our disordered soul. This is what centering prayer does. It shifts our attention from our little ego to god who is eternally in the now.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed