Heaven on Earth: Liturgy and its Symbols

by Alphonso Pinto, S.T.D.

Dr. Alphonso Pinto is a Professor of Theology at Holy Apostles College and Seminary. He holds an S.T.D. in Dogmatic Theology from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome, Italy.

Note from Dr. Chervin: My only regret reading Alphonso Pinto’s chapter is that you, the reader, cannot actually see him in person giving this as a lecture. To fully appreciate the chapter you would need to see his face and his demeanor: casual yet full of dignity; joyful yet profoundly solemn; availably human yet mystically intense. What attracts me most to Dr. Pinto’s teachings are the way he intermingles knowledge of theology, Scripture, music and art. Even without a person to person encounter, that synthesis you will find illuminating as you continue on to pursue this reading.

by Alphonso Pinto, S.T.D.

Dr. Alphonso Pinto is a Professor of Theology at Holy Apostles College and Seminary. He holds an S.T.D. in Dogmatic Theology from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome, Italy.

Note from Dr. Chervin: My only regret reading Alphonso Pinto’s chapter is that you, the reader, cannot actually see him in person giving this as a lecture. To fully appreciate the chapter you would need to see his face and his demeanor: casual yet full of dignity; joyful yet profoundly solemn; availably human yet mystically intense. What attracts me most to Dr. Pinto’s teachings are the way he intermingles knowledge of theology, Scripture, music and art. Even without a person to person encounter, that synthesis you will find illuminating as you continue on to pursue this reading.

In this book you might actually find different viewpoints and styles of Catholicism, professing at one time the variations and unity of the Mystical Body of Christ. My own experience of Catholicism has been made more profound by pursuing graduate studies in Rome. I did not live in a clerical residence/enclave, I lived in the city, rented an apartment, bought food at the wet market . . . and visited the saints, and contemplated Bernini’s masterpieces. In one day, I woke up, got coffee at the local bar, bought my groceries, had amazing prosciutto for lunch, researched for my dissertation, attended mass at a baroque Church, and kissed the hand of Benedict XVI; this is how intense Catholicism can be! It is a lived experience, and not simply a religion that is defended and abstracted. Living in Rome taught me that life flowed from beautiful Liturgy, it punctuated everything we did as students. It is because of this that our lives were intensely symbolic.

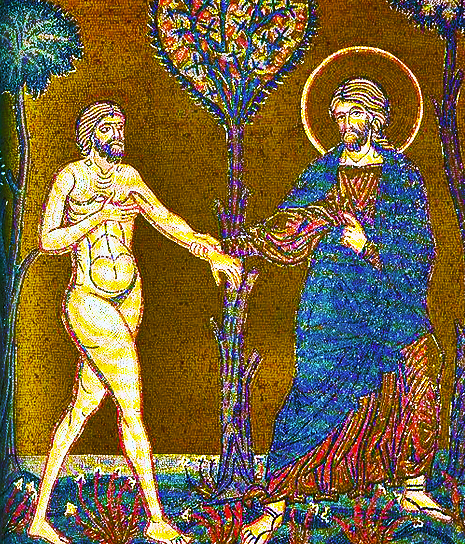

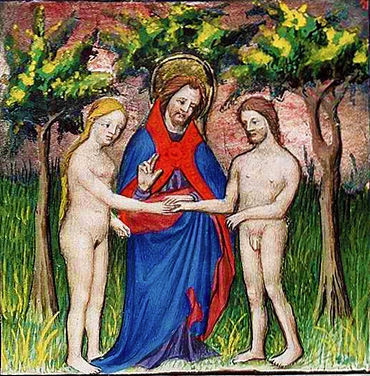

Genesis 3 is a narrative that practically all Catholics know; at least everyone experiences its effects on a daily basis. The outline is quite simple: out of love, God created the universe ex nihilo with man (adam) as the pinnacle of creation. Genesis goes on to describe Adam’s relationship with God as one of communion, where God was accustomed to walk in the garden in the cool of the day; Adam heard his footsteps. There was a conversation between the Creator and the creature that wasn’t one of slavery but really of an exchange of thoughts, and even sentiments, a communion of life. He Who is Eternal has a conversation with a rational creature. God is not aloof from mankind or distant from him by his perfection, omnipotence, majesty and glory; but as breathing life into Adam, endowing him with His image and likeness, God shows how intimately close He is to Adam, and he willed it to be this way. God loved Adam, and saw an image of His Beauty in him. Adam for his part, unlike any creature has a conversatio with God, that is, a way of life that is worthy of God’s presence. Adam was pleasing to God,by his very life, understood the presence of God.

This relationship was broken with the sin of Adam and Eve. The conversation of the first parents was no longer about God, but rather their autonomy from him; they had conversed with the “snake.” In a sense, they believed what the serpent was saying to them about becoming Gods, when in fact, they were already made in the image and likeness of God. Thus, one wonders what kind of “God” did they want to be? The serpent told them that they would know good and evil. It is in this that they would have a radically different conversatio since in Hebrew the verb “to know” is akin to “knowing with experience.”

| They would come to know good by knowing the difference between good and evil through experiencing it. Thus, in Genesis 3, the expulsion from the Garden means a life without experiencing communion with God, without an exchange of ideas, the conversation changes, rather it ends---a common language is not spoken. God’s footsteps are heard in Paradise, causing fear in Adam and Eve. |

The predicament radically changed when Christ became man. The Logos and Son of the Father, the Anointed One from all eternity, spoke to man not in an angelic tongue, but rather, in man’s own language, mostly in Aramaic! Dei Verbum emphasizes that Christ’s communication with man is not simply in words, but in gestures as well. Thus his own words, actions and movements told humanity of God. In Sacred Tradition the context of these actions, especially the sacramental ones; the proper interpretation of a sense and a reference to Scripture are taught in order to portray the meaning Christ gave them.

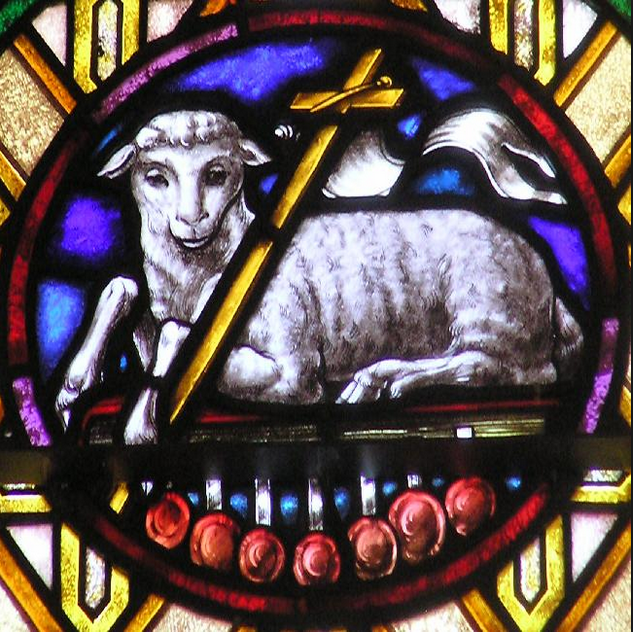

Gestures and words are revealed by God made flesh, that we come to know Him as the Paschal Sacrifice prefigured by the Lamb, the Manna, the Passover Sacrifice. God speaks to man, not as before with the prophets, nor to Moses through the might of light, thunder and wind, but as man. It seems so simple. God can be overlooked by his familiarity, or rather, his self-emptying humility. We can come to understand God through the language of Christ’s own humanity. His actions and words are symbolic of the Father: “He who sees me, has seen the Father [. . .] The words I say to you I do not speak of my own authority; but the Father who dwells in me does his works. Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father in me [. . .]”

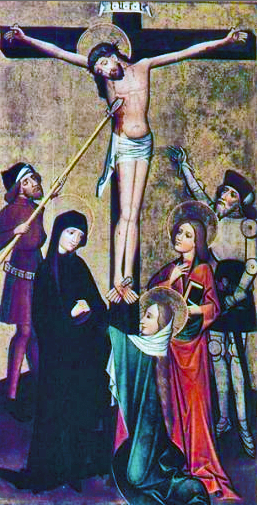

It is within the context of these primal words and actions in which a sacrifice is broken, a libation offered to God the Father, as well as to us in covenant for the remission of our sins and for the participation of our mortal lives with divine life itself, truly and really. The Paschal Mystery of Christ, His Passion, Death and Resurrection is that focal point in history when Adam’s breach is restored, and God as man is able to reconcile man. It is the point where man’s conversation with God was changed. Christ’s Incarnation was meant for that very Hour on the Cross. The reflection of St. Athanasius is quite concise in describing Christ’s Incarnation: “God became man, so that man may become God.” By becoming one of us, is he able to lift up and expiate for all our sins. By becoming one of us, He is able to converse with Us, making himself the model for a new conversatio. As man, Christ’s conversation is a union of divinity and humanity, analogically ours is a union of grace and human nature.

Whereas Adam broke off the communion of life with God by sin, the Son of God restored it through love, sacrificing himself on the Cross. Christ’s communication with us is so intimate that he even offers himself to us as food and drink, “Take this all of you, this is my body [. . .].” In the union of the Body and the Blood of Christ, crucified and risen, with our own mortal flesh and blood, are we made participators of divine life. His life becomes the very source of our life of grace. Are we not tasting heaven? Are we in Paradise, or something more intimately linked to God? A Christian is called to a conversatio higher than Adam by grace, as St.Paul says, “Conversatio nostra in caelis est”—“our conversatio is in heaven.”

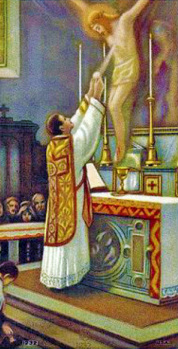

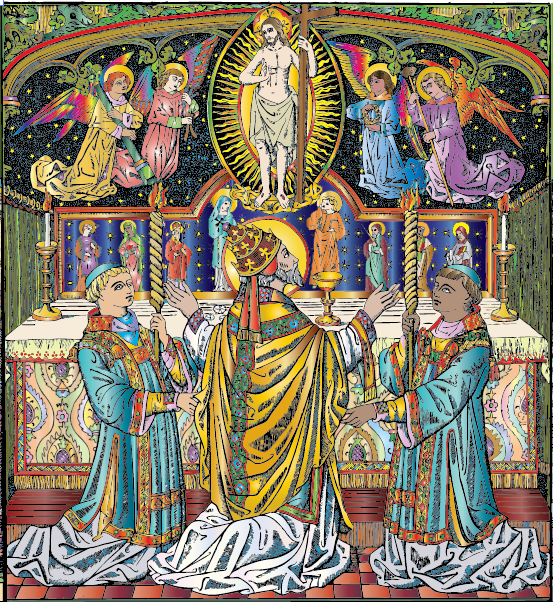

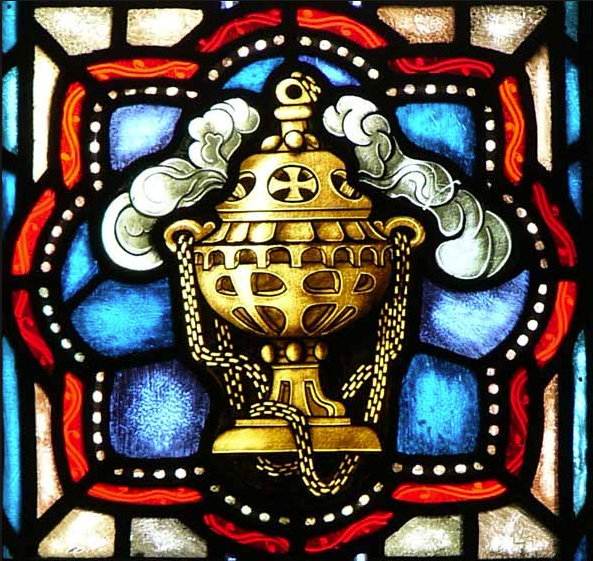

The Liturgy of the Eucharist brings us to this very encounter with Christ. From the first sign of the cross, the Mass consecrates our time, and dedicates it to God. As prayers already lead the worshipper away from the world of mundane cares, they beseech God to be for healing and redemption from the sickness of sins. Through prayer, the lips are cleansed from merely secular words by liturgical hymns and psalms; the ears are filled with Gregorian Chant; the mind is enriched by God’s Eternal word expressed in human words. Old Testament reading is prefigured by the New Testament, culminating in the reading of the Gospel. Incense cleanses our sense of smell, associating the fragrance with the presence of God. Then on the paten, in bread and wine man offers himself through the hands of the priest at the Offertory, but at the Eucharistic Prayer, Christ, through the hands of the priest transubstantiates bread and wine into His Body and Blood. In an unbloody manner, Christ re-presents the sacrifice of Calvary and offers Himself to the Father in expiation for our sins and to mankind for participation of life in Him. At Communion, we taste and receive Him and not bread, not a symbol. The human person is received by God for a new life totally dependent on God. We remain within the Trinity, our senses, intellect and will are seeking a conversion from the earthly to the heavenly.

It is within this sense that the words after the consecration, Mysterium Fidei, “the mystery of faith,” can be understood. These words are not about man offering something to God. It is not about community self-reflection, rather, we are all facing the Mystery of Faith which comes to us through the Eucharist, described in signs and symbols such as sacred art, in vestments, in liturgical instruments and even the priest. At that moment, the center of time is no longer the setting of the sun, the four seasons, the stars’ positions in the sky, the calendar, but the Paschal Mystery of Christ, that is, His Passion, Death and Resurrection made present on the altar.

Ratzinger points out, that it is truly Christ as Shepherd carrying the lost sheep to redemption on his very shoulders in the Liturgy, on Sunday, at every Mass. Hence, the Liturgy is not in our time, rather one is participating in Christ’s time. Thus, Sunday is really the Lord’s Day, and the day of our redemption.

In Early Christianity, the Liturgy was scheduled at Sunday’s dawn, facing the rising sun, that is, ad orientem or facing East. Christians did not look to a city such as Jerusalem or Mecca, rather, they looked to the rising Sun, towards the East, which symbolizes the risen Lord in all his radiance rising from the tomb. He chased away the darkness of sin and death by the effulgence of his own glory. Thus without sin, a new creation was established, where one inherits as an adopted Son of God, eternal life. Thus, Sunday, was not the end of the week, it was rather considered, the beginning of the week which symbolized the beginning of the new creation. This New Day’s dawn represented the sun without setting who is Christ. Facing East in prayer, the Church is on pilgrimage to union with Christ in the New Jerusalem. It is not simply a directional matter, but at its very context is one of the many symbols of a heavenly reality which cannot be possible to grasp except through symbolism,

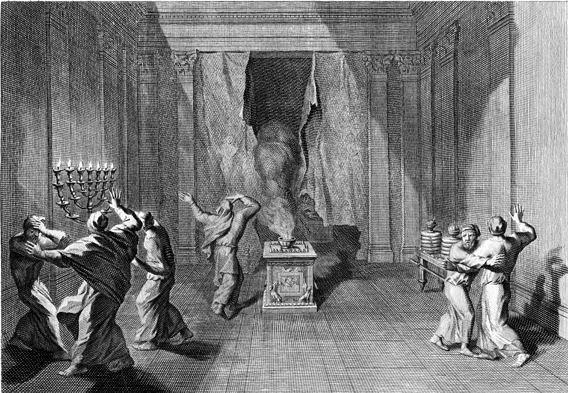

| After the tearing of the Temple curtain and the opening up of the heart of God in the pierced heart of the Crucified, do we still need sacred space, sacred time, mediating symbols? Yes, we do need them, precisely so that, through the “image,” through the sign, we learn to see the openness of heaven. |

A Benedictine abbot, Dom Gérard Calvet explained that the East, incense, the chalice, altarpieces, the candles, and liturgical decoration are sacramentals of our divinization:

Dear friends, think of the lighted candles and the prepared ornaments, does the splendor of our great solemnities stop there? Without a doubt, in its exterior radiance the liturgy is arresting, however, supernatural infused grace dwells in souls through the splendor of the rite. It is such an indescribable gift, and it is the most precious of all the manifestations of our religious culture. This grace is invisible to the eyes of man; it is a sort of interior miracle. [emphasis added]

Like the sun, even liturgical vessels point to a reality of grace beyond themselves. By their decoration they are basically catechetical in teaching us about the beauty that God is bringing about in the souls of the faithful during the Liturgy. It is a formation in a life of grace through the means of beauty.

Dear friends, think of the lighted candles and the prepared ornaments, does the splendor of our great solemnities stop there? Without a doubt, in its exterior radiance the liturgy is arresting, however, supernatural infused grace dwells in souls through the splendor of the rite. It is such an indescribable gift, and it is the most precious of all the manifestations of our religious culture. This grace is invisible to the eyes of man; it is a sort of interior miracle. [emphasis added]

Like the sun, even liturgical vessels point to a reality of grace beyond themselves. By their decoration they are basically catechetical in teaching us about the beauty that God is bringing about in the souls of the faithful during the Liturgy. It is a formation in a life of grace through the means of beauty.

One can come to the understanding of the purpose of our existence through beauty. Praying inside St. Peter’s in Rome at 7:00 am (without the flood of tourists); the quiet of the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi frescoed by Giotto and Cimabue; or the baroque resplendence of the Gesù in the middle of Rome bring the worshipper to a place beyond the local street, or the thoroughfare; leaving behind the vicissitudes of our daily life. The beauty of the art manifests to us that in a church, we are meant to desire heavenly matters. The radiant sun rising in the East, a golden chalice in gothic style, the rose windows of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the ancient gemmed cross of St. Peter’s Basilica representing the glory of the Resurrection, the physical beauty of the Church must remind us of the description of the New Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation:

And in the Spirit he carried me away to a great, high mountain, and showed me the holy city Jerusalem coming down out of heaven from God, its radiance like a most rare jewel, like a jasper, clear as crystal [. . .] and I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb. And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine upon it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb.[Rev 20:10-12, 22-23]

Earthly beauty is a language of the heavenly one, without it, we would not understand the Truth behind the symbolism. Words such as “jasper,” “crystal,” “glory,” have established images on earth, but their beauty portrays an imperfect but yet, metaphorically descriptive image of God’s attributes and that of the New Jerusalem.

And in the Spirit he carried me away to a great, high mountain, and showed me the holy city Jerusalem coming down out of heaven from God, its radiance like a most rare jewel, like a jasper, clear as crystal [. . .] and I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb. And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine upon it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb.[Rev 20:10-12, 22-23]

Earthly beauty is a language of the heavenly one, without it, we would not understand the Truth behind the symbolism. Words such as “jasper,” “crystal,” “glory,” have established images on earth, but their beauty portrays an imperfect but yet, metaphorically descriptive image of God’s attributes and that of the New Jerusalem.

For the 12th century Abbot Suger of St. Denis, his abbey church was a creation of exuberant stone, light and colour as a poetic language of describing the symbolic meaning of a church and its beauty:

Thus sometimes when, because of my delight in the beauty of the house of God, the multicolor loveliness of the gems has called me away from external cares, and worthy meditation, transporting me from material to immaterial things, has persuaded me to examine the diversity of holy virtues, then I seem to see myself existing on some level, as it were, beyond our earthly one, neither completely in the slime of earth nor completely in the purity of heaven. By the gift of God I can be transported in an anagogical manner from this inferior level to that superior one.

Thus sometimes when, because of my delight in the beauty of the house of God, the multicolor loveliness of the gems has called me away from external cares, and worthy meditation, transporting me from material to immaterial things, has persuaded me to examine the diversity of holy virtues, then I seem to see myself existing on some level, as it were, beyond our earthly one, neither completely in the slime of earth nor completely in the purity of heaven. By the gift of God I can be transported in an anagogical manner from this inferior level to that superior one.

On entering a Church, Abbot Suger did not say that he entered a place, akin to any other building, not even akin to the palace, and yet it was not yet the Heavenly Jerusalem itself. The representation of the liturgical ornaments and their outward beauty raises his mind to contemplate a superior reality, that of heaven while affirm his pilgrim state still on earth. Created beauty then can be used as an analogy or metaphor to the heavenly beauty, there is something literary about it. Down to this day, one can visit the Abbey Church of St. Denis, and can visually contemplate through the architecture and stained glass the mysteries of the life of Christ and the doctrines of the Faith. The colours after all these centuries are truly, gem-like. It is such a different world from the hustle and bustle of Paris, no matter how exciting or beautiful that itself can be; St. Denis is contemplation of heavenly reality in stone and glass.

Suger’s abbey church is beautiful and sacred at the same time. Its walls are blest, its floor is sealed, it is the gate of heaven, but not precisely heaven yet; it is not a secular building. It is a building dedicated simply for the glory of God. No earthly king dwells there, but it is where man can finally converse with God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. In a church, human words, literarily as well as artistically, are united to divine message, God is once again walking with man in the cool of the day. He can be analogically understood!

Modernity has lost a sense of the sacred, of dedicating objects, days, or people specifically to God. In our modern culture, do we see Sunday as sacred, that we spend it in the ecclesial church Temple and in the domestic church? Do we celebrate a family meal on Sunday that is founded upon Christ giving himself to us as the bread of life from the altar? Is the Liturgy seen as sacred? Many people see the Eucharist with indifference, singing songs to the Lord that would find a better milieu at a county fair than in a Church.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine chapel is sacred. The walls are filled with saints and their emblems, the just ones are easily distinguishable from the damned; hell is a small corner compared to heaven above, whose radiance finds its source in Christ portrayed in the beauty of Apollo; angels are lifting the resurrected dead from their graves even by the beads of a rosary. All these myriad aspects form one unified whole that professes a stanza in the Creed saying: “He shall come to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom shall have no end.” Colours are varied and not monochrome, emotions of mercy, heavenly ecstasy, despair of condemnation are portrayed in Michelangelo’s skillful design of the contours of faces. If we have lost the sense of the sacred, then the conversation with God will begin to be unintelligible. There will not be a plethora of words, forms, colours, contours informed by our literary vocabulary as expressing the transcendence of God. It is precisely this transcendence that has nurtured a plethora of artistic expressions to describe it.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine chapel is sacred. The walls are filled with saints and their emblems, the just ones are easily distinguishable from the damned; hell is a small corner compared to heaven above, whose radiance finds its source in Christ portrayed in the beauty of Apollo; angels are lifting the resurrected dead from their graves even by the beads of a rosary. All these myriad aspects form one unified whole that professes a stanza in the Creed saying: “He shall come to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom shall have no end.” Colours are varied and not monochrome, emotions of mercy, heavenly ecstasy, despair of condemnation are portrayed in Michelangelo’s skillful design of the contours of faces. If we have lost the sense of the sacred, then the conversation with God will begin to be unintelligible. There will not be a plethora of words, forms, colours, contours informed by our literary vocabulary as expressing the transcendence of God. It is precisely this transcendence that has nurtured a plethora of artistic expressions to describe it.

Even in terms of a death such as Christ’s Crucifixion, Suger of St. Denis wanted to express its salvific value, a mystery, through gold and precious gems, a created reality:

Therefore we searched around everywhere by ourselves and by our agents for an abundance of precious pearls and gems, preparing as precious a supply of gold and gems for so important an embellishment as we could find, and convoked the most experienced artists from diverse parts. They would with diligent and patient labor glorify the venerable cross on its reverse side by the admirable beauty of those gems; and on its front—that is to say in the sight of the sacrificing priest—they would show the adorable image of our Lord the Saviour, suffering, as it were, even now in remembrance of His Passion.

The exuberance of created things, finite but beautiful, is supposed to portray in its refraction of varied light the radiance of divine glory which no man has seen. If one sees the Crucifixion, was present at the historical event, one would see the Son of God, willfully bowing his head in death, accomplishing the mission which He was given. Yet, there is more to be understood about the mystery than merely the physical observations of the execution. Abbot Suger describes the glory of Christ as Saviour hidden by the darkness of Calvary through the beauty of gems. Abbot Suger does not state how much the cross cost, he does not show us a receipt, but the preciousness of gems is not measured by price, but how it can be used metaphorically to portray the glory of the Cross. Human ingenuity portrays in a proper manner what in reality is uncircumsribable by the self-giving generousity of divine love.

Therefore we searched around everywhere by ourselves and by our agents for an abundance of precious pearls and gems, preparing as precious a supply of gold and gems for so important an embellishment as we could find, and convoked the most experienced artists from diverse parts. They would with diligent and patient labor glorify the venerable cross on its reverse side by the admirable beauty of those gems; and on its front—that is to say in the sight of the sacrificing priest—they would show the adorable image of our Lord the Saviour, suffering, as it were, even now in remembrance of His Passion.

The exuberance of created things, finite but beautiful, is supposed to portray in its refraction of varied light the radiance of divine glory which no man has seen. If one sees the Crucifixion, was present at the historical event, one would see the Son of God, willfully bowing his head in death, accomplishing the mission which He was given. Yet, there is more to be understood about the mystery than merely the physical observations of the execution. Abbot Suger describes the glory of Christ as Saviour hidden by the darkness of Calvary through the beauty of gems. Abbot Suger does not state how much the cross cost, he does not show us a receipt, but the preciousness of gems is not measured by price, but how it can be used metaphorically to portray the glory of the Cross. Human ingenuity portrays in a proper manner what in reality is uncircumsribable by the self-giving generousity of divine love.

The Liturgy even teaches that our very being is symbolic in relation to Christ: “May we who mystically represent the Cherubim, and sing the thrice-holy hymn, to the Life-Creating Trinity, now set aside all earthly cares. That we may welcome the King of All invisibly escorted by angelic hosts, Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.” This hymn portrays the worshipper as representing angels before God. In this sense, tangible human voice at Mass represents mysterious angelic praise. Once again, human worship takes its cue from heavenly worship and thus has to reflect not only in intention but even in the perfection of artistry, the angelic worship.

“Church on Sunday” affirms the sacred, affirms God, and it doesn’t affirm the primacy of our daily cares, worries, and secularity; we must make sure we recognize who the “Sun” is, and what or whom does He illuminate. A blessing before meals affirms God’s benefices. A day is separated solely for Him, and yet we do not relate to him as to any other human, because we have to relate to Him as God. In Christ it is God who related to us as man, so that we can come to understand and to love, Father, Son and Spirit through the message of his Incarnation.

“Church on Sunday” affirms the sacred, affirms God, and it doesn’t affirm the primacy of our daily cares, worries, and secularity; we must make sure we recognize who the “Sun” is, and what or whom does He illuminate. A blessing before meals affirms God’s benefices. A day is separated solely for Him, and yet we do not relate to him as to any other human, because we have to relate to Him as God. In Christ it is God who related to us as man, so that we can come to understand and to love, Father, Son and Spirit through the message of his Incarnation.

Symbolism, especially in sacred art, in the extravagant beauty of liturgical objects is not about wealth or riches. It was not meant to be a show of one’s social status. Rather, sacred art expresses the ineffable in a very profuse and exuberant way, the baldacchino of St. Peter’s Basilica accentuates the transcendent dignity of the Holy Sacrifice. It places our senses and intellect in relation to sacredness and its dignity. Josef Pieper points out that,

Rejoicing that is skimping and sparing is no rejoicing at all. Yet again, splendor and magnificence of not necessarily mean extravagant expenses, though such are not excluded. In no wise, or course, should that kind of extravagance be construed as an ostentatious display of wealth and riches. We mean the spontaneous expression of an inner richness, indeed, of that richness flowing from experiencing the true presence of God among his people.

In comparison to the in-finitude of Divine Beauty, created beauty is but a very poor imitation of the actual and ineffable divine reality that it is supposed to portray. God’s beauty is not part of this world, though created beauty does bear its vestige. It bears the trace of Divine Beauty as a pot bears the imprint of the fingers of the potter. Where does this beauty lead but love. In its declaration on the veneration of sacred relics and images, the Council of Trent expressed that sacred images, are not ends in and of themselves. They are means through which one can love God through devotion, and so, sacred images, liturgical vessels, the decoration of churches have to be based upon the Truth as revealed to us by Christ, which has Truth at it very source.

There can be no true devotion without love.

Rejoicing that is skimping and sparing is no rejoicing at all. Yet again, splendor and magnificence of not necessarily mean extravagant expenses, though such are not excluded. In no wise, or course, should that kind of extravagance be construed as an ostentatious display of wealth and riches. We mean the spontaneous expression of an inner richness, indeed, of that richness flowing from experiencing the true presence of God among his people.

In comparison to the in-finitude of Divine Beauty, created beauty is but a very poor imitation of the actual and ineffable divine reality that it is supposed to portray. God’s beauty is not part of this world, though created beauty does bear its vestige. It bears the trace of Divine Beauty as a pot bears the imprint of the fingers of the potter. Where does this beauty lead but love. In its declaration on the veneration of sacred relics and images, the Council of Trent expressed that sacred images, are not ends in and of themselves. They are means through which one can love God through devotion, and so, sacred images, liturgical vessels, the decoration of churches have to be based upon the Truth as revealed to us by Christ, which has Truth at it very source.

There can be no true devotion without love.

Being struck and overcome by the beauty of Christ is a more real, more profound knowledge than mere rational deduction. Of course we must not underrate the importance of theological reflection, of exact and precise theological thought; it remains absolutely necessary. But to move from here to disdain or to reject the impact produced by the response of the heart in the encounter with beauty as a true form of knowledge would impoverish us and dry up our faith and our theology. We must rediscover this form of knowledge; it is a pressing need of our time.

The Beauty of our symbols attracts us to the Truths that they portray. They are encounters with Christ! They entice us to discover why it is that they are mysteries. Why does the stained glass of Chartres remind me of heaven? What is it of heaven represented in the stained glass? Upon what earth do my feet tread? Am I in Paradise?

It is at this point, in the midst of Chartres, do we have to retrace out footsteps back to Adam, Eve, the snake and the garden. In the fallen state, I cannot see. Was I meant to be separated from the love of God? Can I find fulfillment in God? What is it like to converse with him? What are we doing then, in terms of communicating with God and why is God communicating to us.

The Beauty of our symbols attracts us to the Truths that they portray. They are encounters with Christ! They entice us to discover why it is that they are mysteries. Why does the stained glass of Chartres remind me of heaven? What is it of heaven represented in the stained glass? Upon what earth do my feet tread? Am I in Paradise?

It is at this point, in the midst of Chartres, do we have to retrace out footsteps back to Adam, Eve, the snake and the garden. In the fallen state, I cannot see. Was I meant to be separated from the love of God? Can I find fulfillment in God? What is it like to converse with him? What are we doing then, in terms of communicating with God and why is God communicating to us.

We first have to begin with the Incarnation. It was in the first Adam that we knew/experienced how to distance ourselves away from God. The experience of the Bible shows that from the very beginning, sins multiplied: after the original sin came the slaying of Cain, then came the causes of the Great Flood, etc. To establish a new order God became man and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth. I can personally encounter the Son of God. Man is now much more intimately close to Jesus Christ who shared our humanity. It was the God who established this new relationship, which was impossible for man to do. Liturgically, Christ is the priest who offers Himself up as a sacrifice, granting us his very life for our participation in eternal life. The Cross and the Mass are one and the same. Christian worship is essentially Christological at its very core, there is no Church without Christ as high priest who enters into a heavenly sanctuary offering a perfect sacrifice:

But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) he entered once for all into the Holy Place taking not the blood of goats and calves, but his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. [Hebrews 9:11-12]

But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) he entered once for all into the Holy Place taking not the blood of goats and calves, but his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. [Hebrews 9:11-12]

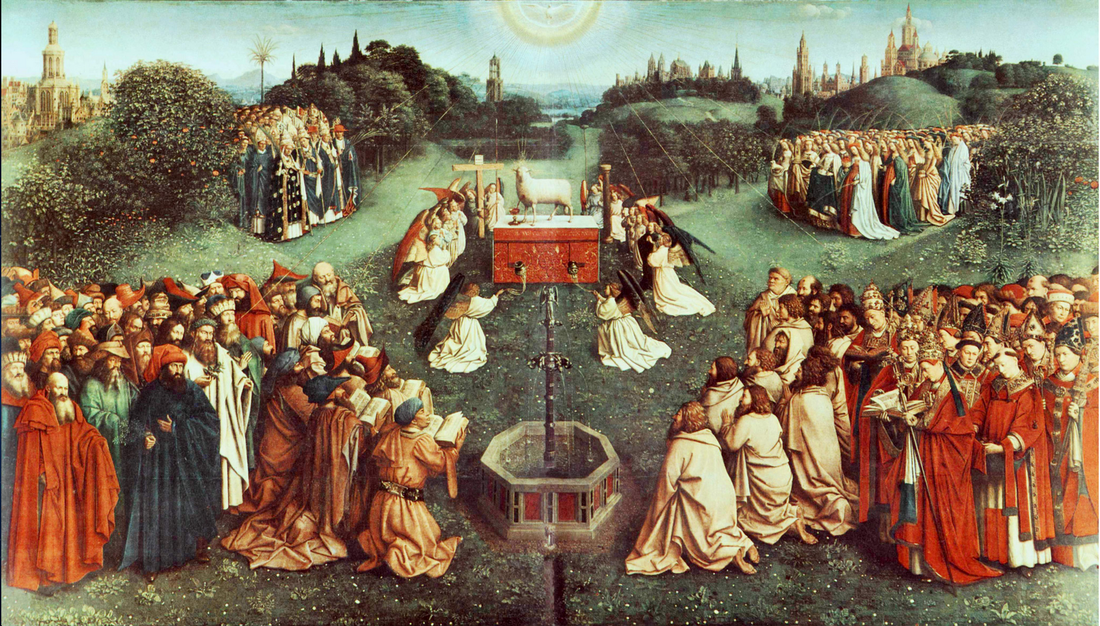

In Revelation, the emphasis is on Christ as Victim of an eternal Liturgy, in fact, He is the Paschal Lamb. However, in one image is his passion, death and resurrection portrayed.

And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders, I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain, with seven horns and with seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of god sent out into all the earth; and he went and took the scroll and the right hand of him who was seated on the throne. And when he had taken the scroll, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, ad with golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints; and they sang a new song, saying, “worthy art thou . . .” [Rev 5:6-9]

And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders, I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain, with seven horns and with seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of god sent out into all the earth; and he went and took the scroll and the right hand of him who was seated on the throne. And when he had taken the scroll, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, ad with golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints; and they sang a new song, saying, “worthy art thou . . .” [Rev 5:6-9]

A lamb standing slain is a Paschal/Passover Sacrifice that is alive and risen. He is standing in the sanctuary of heaven, unlike all the other sacrifices that have gone before him, slain but alive. Having conquered death, his life then is eternal. As a Paschal Victim, Christ is both Lamb and bread to the Christian at Mass. In the whiteness of what seems like bread, offered during the Eucharistic prayer, is Christ’s body; what seems as wine, is His blood. This is no longer symbol, this is a Sacrament. The Body of Christ on a golden paten. Christ, in the hands of the priest, presents himself to us for eternal life. The simple act of Communion portrays something even more profound. Christ offers himself to us, notice we do not take him with our hands, but rather he is given to us, or “handed over to us,” reminiscent of when he handed himself over for our salvation. The response of Amen, or just simply the reception of communion is not only a virtuous act of Faith, but also saying, “This is my own self, my life, whatever I can offer you.” In truth, it is He who receives us.

In communion, what we have is greater than symbol. It is more precious than the gemmed chalice and paten, purer than the altar linen upon which it was laid. More glorious than the church that surrounds the sacred mysteries; what we have is God Himself as sacrifice which we receive. The sacred imagery and symbolism surrounding and jubilantly exclaiming this sacrifice assists us in experiencing the Mystery of Faith which is re-presented before us, “we do indeed participate in the heavenly liturgy, but this participation is mediated to us through earthly signs, which the Redeemer has shown to us as the place where his reality is to be found.” Everything from the beauty of the wax of bees, to the fine altar linen, gold and gems from the earth, glass and painting from the ingenuity of man, singing united to the angels; this is how we come to know and desire, the Mystery of Faith.

For Personal Reflection and Group Sharing:

Examine Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, how is it related to my experience of Mass in the parish? Look at its colours, look at Christ. Why is the Last Judgment on the Eastern Wall? Compare the saints to Christ; how is Christ’s beauty reflected in their beauty? Look at Christ’s complexion, his face, his radiance. Do a bit of research to figure out the pigments from which it was made, the techniques, and read about the importance of portraying the Last Judgment in Church. Is there any reason why we do not see the Last Judgment portrayed in churches today, what could be the change in attitude. How does this work of art help me relate to the Second Coming of Christ?

Examine Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, how is it related to my experience of Mass in the parish? Look at its colours, look at Christ. Why is the Last Judgment on the Eastern Wall? Compare the saints to Christ; how is Christ’s beauty reflected in their beauty? Look at Christ’s complexion, his face, his radiance. Do a bit of research to figure out the pigments from which it was made, the techniques, and read about the importance of portraying the Last Judgment in Church. Is there any reason why we do not see the Last Judgment portrayed in churches today, what could be the change in attitude. How does this work of art help me relate to the Second Coming of Christ?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed