by

Fr. Dennis Koliński, SJC

After completing undergraduate studies at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point in 1974, Fr. Koliński did postgraduate study at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland where he received an M.A. in Slavic ethnography. Many years later, perceiving a call to the religious life and the priesthood, Fr. Koliński became one of the founding members of the Canons Regular of St. John Cantius, a new religious community of men that was founded at St. John Cantius Parish in Chicago in 1998. He received his M.Div. degree following the completion of his seminary studies at Holy Apostles Seminary in Cromwell, Connecticut and was ordained to the priesthood in 2004. After serving as an associate pastor at St. John Cantius Parish in Chicago, Fr. Koliński was appointed in 2007 as pastor of his community’s second parish, St. Peter’s in Volo, Illinois. Since 2010, he has been assigned to Holy Apostles Seminary and College as formator and academic advisor for the seminarians of the Canons Regular of St John Cantius. He is also a member of the seminary faculty and helps in seminary formation.

Note from Dr. Chervin: Fr. Kolinski, S.C.J., teaches liturgy at Holy Apostles College and seminary. I asked him if he would write a chapter on this subject in addition to the chapter on the Spirituality of John Paul II which you will read later in this book. He didn’t have time to write another chapter but said that I could place here two papers he wrote years ago. I think you will agree that these papers of Fr. Koliński shed light on the reason behind some of the liturgical issues so current in our Church today.

In the early twentieth century, Pope Pius X’s call for a restoration of the “true Christian spirit” by means of “active participation in the holy mysteries and in the public and solemn prayer of the Church,” led to what became known as the Liturgical Movement and laid the groundwork for the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium). It was the desire of the Council “to undertake with great care a general restoration of the liturgy itself.” (SC, 21) And in doing so, the Council specifically asked “that sound tradition may be retained” (SC, 23) because “in the earthly liturgy we take part in a foretaste of that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem,” (SC, 8) a sacred action surpassing all others, “of Christ the priest and of His Body, the Church.” (SC, 7) Renewal is always necessary, especially in the modern world, but in recent years, many have questioned whether it has taken the correct course. In 2007, the secretary of the Vatican’s Congregation for Divine Worship, Archbishop Albert Malcom Ranjith, admitted that liturgical reform after Vatican II “has not been able to achieve the expected goals.” (CWN, 23 February 2007) It is for this reason that a “new liturgical movement” has arisen, which strives to be true to both the Council’s directives, as well as to “sound tradition.” The following two articles can, therefore, help shed some light on the nature of the liturgy itself by taking a look at two important aspects of the Church’s centuries-old liturgical tradition.

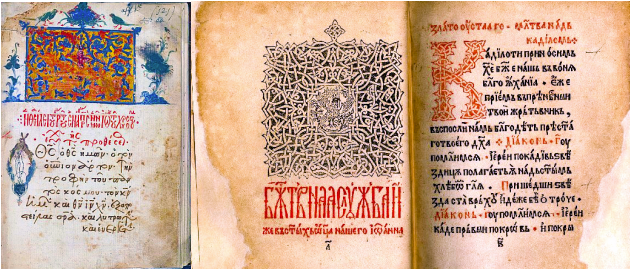

Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom

Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom The ancient Roman Rite of the liturgy, which we know best, was initially a liturgical form that was limited to a relatively small part of the early Christian world. It was characterized by “simplicity, practicality, a great sobriety and self-control, gravity and dignity,” which was a reflection of the ancient Roman disposition.2 And this rite, in turn, had its own variations. The most famous of them was the Ambrosian Rite celebrated in the city of Milan, most likely since the fourth century.

Contrary to what some have thought, the liturgies of the Early Church were not based upon improvisation by the celebrating bishop. Rather, research has shown a striking uniformity in certain key elements of the liturgy already at a very early date, and in the major centers of Christianity the liturgy was uniform to a great extent already by the first or early second century—especially in the Eucharistic Sacrifice itself.3 A number of liturgical texts have come down to us from that period and the prayers, which they contain, display an unusual beauty.

All of these liturgies, in one way or another, incarnated a sense of the transcendent and evoked an inexpressible awe for the ancient Christians. The rituals of the Sacred Mysteries expressed otherworldly realities and showed that the Patristic era clearly possessed a concept of the “sacred.” Certain spaces, words and rituals were sacred not only because of what they represented but also because they actually embodied the inexpressible mystery of the Eucharist. Mystery was at the root of the liturgy and mystery defined what was sacred.

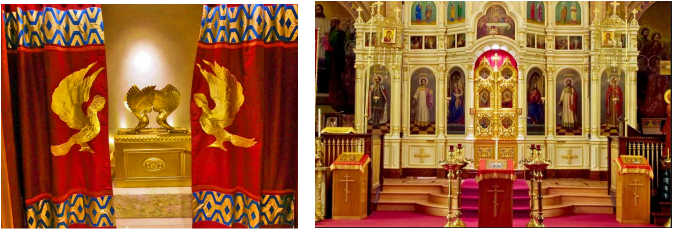

The priests of the Old Covenant served “a copy and shadow of the heavenly sanctuary.”12 They were aware that the rituals, which they performed in the Holy of Holies, took place “outside of time and matter, in the realm of the angels and the heavenly throne.”13 The high priest entered the Holy of Holies in great fear and awe. Because the sanctuary of the New Covenant was not a different sanctuary, but merely a clearer manifestation of the same heavenly reality—the image in contrast to the shadow—priests in early Christian times were likewise filled with fear and awe as they entered the sanctuary for the celebration of the Sacred Mysteries. Writings of the Patristic Age speak of “the most awful sacrifice” and “the great fearful holy life-giving awful sacrifice.”14,15

The arrangement of sacred buildings, the manner of executing the sacred rituals and the words that the ancient Christians used in the sacred liturgies show us that they worshipped with an acute awareness of the sacred.

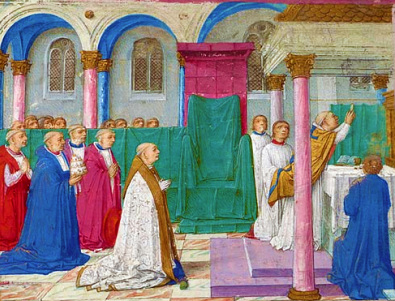

Behind the altar in the middle of the sanctuary apse stood the bishop’s throne, with seats for his presbyters on both sides in a semi-circle. He sat at the head of the assembly because he was the helmsman of the ship.22 Directly above him mosaics adorned the dome of the apse with representations of Christ—either as the Pantocrator (in the East) or the Lamb of God (in the West). The location of these images on the eastern wall of the church also had great significance, for Christians of the first century believed that during the Sacred Mysteries they were turning toward Christ, “who ascended up to the heaven of heavens to the east.” 23,24

So mysterious, so holy was this sacred ritual, which united earth with heaven, that in the Early Church the holy “Mystery” was concealed from catechumens and pagans as much as possible.27 It was a highly private activity, which necessarily excluded all strangers.28 Only the baptized, those who were in full communion with the Church, both earthly and heavenly, were present.29 Only those, who fully understood what was happening could attend.

After the homily, the deacon exclaimed, “Let none of the catechumens, let none of the hearers, let none of the unbelievers, let none of the heterodox, stay here.”30 Then, after all of the unbaptized had left, the deacons and subdeacons stood at the doors to the church “lest any unbeliever, or one not yet initiated, come in.”31 They warned lest “no one stay in hypocrisy,” and that all “stand in fear and trembling.”32 Only after the catechumens, public penitents and pagans had left the church did the deacons draw back the curtains, which had concealed the altar, “uncovering the veils that darkly invest in symbol this sacred ceremonial.”33

The need for purity was especially important for the priests who ministered at the altar. St. Cyprian was uncompromising on this point. He said that if the Levitical priests of the Old Covenant were forbidden to approach the altar if they were guilty of serious sin, how much more must the priests of the New Covenant be unblemished as they approach the Holy Mysteries. So holy was the altar of sacrifice that those guilty of serious sin “may not return again to the profanation of the altar.”36 The sacredness of the ritual demanded a reflection of the sacred within the priest himself, for he “call[ed] down the Holy Spirit over the Holy Sacrifice, while angels surround[ed] the altar!”37 It was as if he were already entering heaven—and in a sense, he truly was.

The unseen spiritual realities of the Mysteries expressed themselves through the physicality of the ritual. The manner in which the body expressed itself liturgically “[made] the essence of the liturgy, as it were, bodily visible.”38 Bodily gestures and ritualistic motions bore spiritual meaning. Postures, gestures, ritual garb, the layout of physical space, and the position taken for various liturgical actions were not arbitrary or superfluous because they were sacred. For the ancients, they all took on a symbolic ritual significance for they were physical expressions of spiritual realities—an image of the heavenly reality. The “physicality” of ritual practices that took place within the sacred spaces affected the body in perceptible ways, so that Christians could see and feel their spiritual endeavors.39

Traditionally, the task of deacons was to tell the congregation what postures the people were to assume. Appropriate physical expressions encouraged appropriate interior attitudes.47 The deacons were to “oversee the people, that nobody may whisper, nor slumber, nor laugh, nor nod; for all ought in the church to stand wisely, and soberly, and attentively.”48 When they drew back the curtains, which had previously hid the sanctuary and altar, all of the faithful fell to their knees.49

When the time came to distribute Communion, the bishop showed the Sacred Host to the people and the deacon exclaimed, “The Holy of Holies!” St. John Chrysostom wrote that the faithful must approach the Eucharist with awe and devotion.50 He wrote: “Reflect, o man, what sacrificial flesh you take in your hand! To what table you approach.”51 Everyone was to approach the altar “with reverence and holy fear, as to the body of their king.”52 To each person the deacon said, “Approach in the fear of the Lord” because he was to partake not of earthly bread, but of “heavenly and immortal food.”53,54

St. John Chrysostom excelled in expressing the sacred mystery of the Eucharist. He wrote that it was an “awe-inspiring and divine table,” “a table of holy fear,” upon which took place the “ineffable mysteries,” the “frightful mysteries,” the “mysteries that demand reverence and trembling.”55,56 For him, the meaning of the word “mystery” even took on the nuance of “tremendous,” “He whom the angels do not see without trembling and do not dare to gaze on without fear because of the brightness that radiates from him, him we take as food, we receive him, we become one body and one flesh with Christ.”57,58

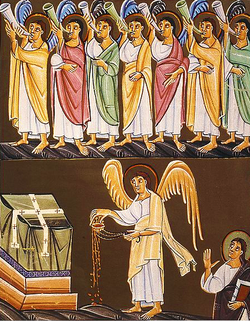

In their writings, the Fathers of the Church were unambiguous in their understanding that what happened on the altar during the Eucharistic sacrifice was something far from ordinary. It was an entry into the liturgy of heaven. On the altar Christ entered into the assembly through the torn curtain. It was the place where heaven opened up, leading them into the eternal liturgy.65 One of the most striking aspects of the ancient liturgical prayers which exemplify this, is their vivid and effusive descriptions of the heavenly realities unfolding in the sanctuary: “Round Thee stand ten thousand times ten thousand, and thousands of thousands of holy angels and hosts of archangels; and Thy two most honored creatures, the many-eyed cherubim and the six-winged seraphim.”66 “The numberless army of Angels … the Cherubim and six-winged Seraphim … together with thousands of thousand Archangels and myriad myriads of Angels.”67

Throughout the liturgy, ancient Christians heard references to hidden mysteries and secret words.68 They knew that when they were present at the Sacred Mysteries of the Eucharist, they were in the presence of “the unutterable One, the incomprehensible One … before whom all that is high falls down and remains silent … and beholding whom all creation surrenders in silent adoration.”69 Contemplation of this mystery directed and stimulated their lives and the liturgy was lived and practiced by the Early Church in an attitude of objective piety.70

The prayers, the gestures and postures, the acts of reverence used in the early Christian Church all cultivated an awareness of holy mystery. Its churches created a sacred space, which took them out of the everyday world and placed them before the heavenly altar surrounded by myriads of angels. The words, which the Fathers of the Church used to express the reality in which they were taking part put them in the realm of the sacred. For them, the liturgy expressed something beyond this world by embodying a sense of transcendence and inexpressible awe. They knew that they were in the presence of the One God and Sovereign of all, “who sittest upon the cherubim, and art glorified by the seraphim, before whom stand thousand thousands and ten thousand times ten thousand hosts of angels and archangels.”71

St. Ambrose, Theological and Dogmatic Works: The Sacraments, The Mysteries (The Catholic University of America Press: Washington, D.C., 1963).

Baker, Margaret. “The Temple Roots of the Liturgy,” (Online resource, Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism Project, Marquette University, 2003).

Baur, Chrysostomus, OSB, John Chrysostom and His Times, vol. I (The Newman Press: Westminster, Maryland, 1959).

Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book II, Section VII, Paragraph LVII (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book VIII, Section II, paragraph XII (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

St. Cyprian, Epistle LXIII (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

Divine Liturgy of St. James (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

The Divine Liturgy of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist Mark, The Disciple of the Holy Peter (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

Dix, Dom Gregory, The Shape of the Liturgy (Dacre Press: London, 1945).

The Early Christians after the Death of the Apostles, ed. Eberhard Arnold (Plough Publishing House: Rifton, N.Y., 1970).

Encyclopedia of the Early Church, ed. Angelo Di Berardino (Oxford University Press: N.Y., 1992).

Fortescue, Adrian, “Antiochene Liturgy,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. I (Robert Appleton Company, 1907, Online Edition, 2003).

Fortescue, Adrian, “Liturgy,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. IX (Robert Appleton Company, 1908, Online Edition, 2003).

Fortescue, Adrian, “Liturgy of Jerusalem,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. VIII (Robert Appleton Company, 1910, Online Edition, 2003).

Introduction to the Liturgy, ed. Anscar J. Chupungco, O.S.B. (The Liturgical Press: Collegeville, Minn., 1997).

Jenner Henry, “Ambrosian Liturgy and Rite,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. I (Robert Appleton Company, 1907, Online Edition, 2003). 12

St. John Chrysostom, Instructions to Catechumens (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church,” Copyright © 1999).

Kinross, Lord, Hagia Sopia (Newsweek: N.Y., 1972).

Martimort, A.G., “Structure and Laws of the Liturgical Celebration,” The Church at Prayer: An Introduction to the Liturgy, vol. I—Principles of the Liturgy (The Liturgical Press: Collegeville, Minn., 1987).

The Mystery of Christian Worship: and other writings, ed. Burkhard Neunheuser, O.S.B. (The Newman Press: Westminster, Maryland, 1932).

Neunheuser, Burkhard, O.S.B., “Roman Genius Revisited,” Liturgy for the New Millenium (The Liturgical Press: Collegeville, Minn., 2000).

Quasten, Johannes, Patrology, vol. III (The Newman Press: Westminster, Maryland, 1960).

Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal, The Spirit of the Liturgy (Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 2000).

Thurston, Herbert, “Symbolism,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. IV (Robert Appleton Company, 1912, Online Edition, 2003).

Torevell, David, Losing the Sacred: Ritual, Modernity and Liturgical Reform (T & T Clark Ltd.: Edinburgh, 2000).

Endnotes

1. Encyclopedia of the Early Church, ed. Angelo Di Berardino (Oxford University Press: N.Y., 1992), 293.

2. Neunheuser, Burkhard, O.S.B., “Roman Genius Revisited,” Liturgy for the New Millenium (The Liturgical Press: Collegeville, Minn., 2000), 43.

3. Fortescue, Adrian, “Liturgy,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. IX (Robert Appleton Company, 1908, Online Edition, 2003).

4. The Mystery of Christian Worship: and other writings, ed. Burkhard Neunheuser, OSB (The Newman Press: Westminster, Maryland, 1932), 34.

5. Ibid, 35.

6. Encyclopedia of the Early Church, 495.

7. Ibid, 495.

8. Ibid, 577.

9. Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal, The Spirit of the Liturgy (Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 2000), 60.

10. Hebrews 9:23.

11. Hebrews 9:24.

12. Hebrews 8:5.

13. Baker, Margaret. “The Temple Roots of the Liturgy,” (Online resource, Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism Project, Marquette University, 2003).

14. From St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in Baker, “The Temple Roots”

15. From the Nestorian liturgy, in Baker, “The Temple Roots”

16. Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book II, Section VII, Paragraph LVII (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”). Our word “nave” comes from the Latin word for ship, navis.

17. Baur, Chrysostomus, O.S.B., John Chrysostom and His Times, vol. I (The Newman Press: Westminster, Maryland, 1959), 196.

18. Divine Liturgy of St. James (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

19. Exodus 26:31-34.

20. Hebrews 9:4.

21. Kinross, Lord, Hagia Sopia (Newsweek: N.Y., 1972), 15.

22. Thurston, Herbert, “Symbolism,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. IV (Robert Appleton Company, 1912, Online Edition, 2003).

23. St. Ambrose, Theological and Dogmatic Works: The Sacraments, The Mysteries (The Catholic University of America Press: Washington, D.C., 1963), 7.

24. Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book II.

25. Dix, Dom Gregory, The Shape of the Liturgy (Dacre Press: London, 1945), 28. Taken from St. Ignatius’ Epistle to the Magnesians: VI.I.

26. Ratzinger, The Spirit, 61.

27. Baur, John Chrysostom, 194.

28. Dix, The Shape, 16.

29. Fortescue, “Liturgy”.

30. Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book VIII, Section II, paragraph XII (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

31. Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book II.

32. Fortescue, Adrian, “Antiochene Liturgy,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. I (Robert Appleton Company, 1907, Online Edition, 2003).

33. Divine Liturgy of St. James.

34. Encyclopedia of the Early Church, 494.

35. St. John Chrysostom, Instructions to Catechumens: 2 (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church,” Copyright © 1999).

36. St. Cyprian, Epistle LXIII.3 (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

37. Baur, John Chrysostom, 183.

38. Ratzinger, The Spirit, 176-177.

39. Torevell, David, Losing the Sacred: Ritual, Modernity and Liturgical Reform (T & T Clark Ltd.: Edinburgh, 2000), 48-49.

40. Introduction to the Liturgy, ed. Anscar J. Chupungco, O.S.B. (The Liturgical Press: Collegeville, Minn., 1997), 76. 14

41. Martimort, A.G., “Structure and Laws of the Liturgical Celebration,” The Church at Prayer: An Introduction to the Liturgy, vol. I—Principles of the Liturgy (The Liturgical Press: Collegeville, Minn., 1987), 180.

42. Introduction to the Liturgy, 76.

43. Divine Liturgy of St. James.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid.

46. The Divine Liturgy of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist Mark, The Disciple of the Holy Peter (Online Edition, New Advent, “The Fathers of the Church”).

47. Martimort, “Structure and Laws”, 180.

48. Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book II.

49. Baur, John Chrysostom, 192.

50. From Homilia de baptismatis Christi, MG 49,379, in Quasten, Johannes, Patrology, vol. III (The Newman Press: Westminster, Maryland, 1960), 480.

51. Quasten, Patrology, 480.

52. Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, Book II.

53. Fortescue, “Antiochene Liturgy”.

54. The Divine Liturgy of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist Mark.

55. Quasten, Patrology, 480.

56. From St. John Chrystosom, in Quasten, Patrology, 480.

57. Encyclopedia of the Early Church, 577.

58. From St. John Chrysostom’s Homily 82 on Matthew 5, in Encyclopedia of the Early Church, 441.

59. Quasten, Patrology, 480.

60. Encyclopedia of the Early Church, 441.

61. Quasten, Patrology, 480.

62. Ibid.

63. Encyclopedia of the Early Church, 504.

64. Ratzinger, The Spirit, 60.

65. Ibid, 71.

66. The Divine Liturgy of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist Mark.

67. Fortescue, “Antiochene Liturgy”.

68. From the Acts of Thomas I.10, in The Early Christians after the Death of the Apostles, ed. Eberhard Arnold (Plough Publishing House: Rifton, N.Y., 1970).

69. From Acts of John 84, 84, 79, in The Early Christians, 235.

70. Encyclopedia of the Early Church, 495.

71. Divine Liturgy of St. James.

Questions for Personal Reflection and Group Sharing:

1. How did the Early Church understand the nature of the sacred liturgy?

2. How was the liturgy of the New Covenant foreshadowed in the worship of the Old Covenant Temple?

3. How do the sensate elements of the liturgy help Catholics properly and more fully experience the Mass?

RESPONSES TO THIS CHAPTER:

Response of Sean Hurt:

The unseen spiritual realities of the Mysteries expressed themselves through the physicality of the ritual. The manner in which the body expressed itself liturgically “[made] the essence of the liturgy, as it were, bodily visible.”

When I first started attending masses, before I even started RCIA, I mostly ignored the liturgical movements. Things like genuflection, an offering or opening gesture, even the sign of the cross I didn’t really participate. I thought, “This is not how I show respect, holiness etc. Should I do it just because everyone else does? That wouldn’t be genuine.”

It wasn’t until I met Ronda’s sister who teaches sacred dance that I really understood the importance of these gestures. She taught me that we can pray through movement. In fact that is an important aspect of prayer. Jesus taught us to love God with our whole being. So, doesn’t it make sense to pray with our bodies as well?

Now, we normally assume our minds control our bodies. But I think it’s a two-way street. Outward actions (such as dance and gestures) can shape our interior self. For example, there is something inherent to genuflection that builds an inward respect for our Lord. It seems to me that action and belief reinforce each other, rather than one simply causing the other. So, it’s fascinating to me how the early Church recognized this, and placed such emphasis on movement.

Response from Kathleen Brouillette:

I am tempted to write, “this is a recording” because my reaction to these chapters on liturgy is the same as it has been to all the preceding chapters: our beloved Holy Mother Church needs to do a better job of forming her people in the truth. A significant part of that truth, the image of Christ as Bridegroom of the Church and Head of His Body, the Church, is noted in the introduction to Fr. Kolinski’s paper: “…‘in the earthly liturgy we take part in a foretaste of that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem,’ a sacred action surpassing all others, ‘of Christ the priest and of His Body, the Church.’ ”

A clear and deep understanding of that truth would do much to change the celebration of liturgy today, when mankind takes so much for granted and is especially impressed with his own ability to understand and master the world in which he lives. There is precious little sense of mystery and awe, and very little fear of the Lord, who is being systematically removed from every aspect of life in the twenty-first century, as I have written before.

In Fr. Kolinski’s course (taught at Holy Apostles on campus and also on-line in the Distance Learning program) on organic development of the liturgy, he taught that the Church and Her liturgy are a living and growing entity, evolving over time. However, removal of so much of the beauty and awe in language, architecture, art, music, and such has also removed much of the mystery and reverence on the part of the people. Fewer are attending Mass with any regularity, or exhibiting any outward expression of holy fear. We are not taught the privilege of being in the Presence of such a great mystery, as they were in the early Church. How many people strike their breasts as they say, “through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault”? How many follow a Eucharistic fast? How many even rid their mouths of gum or candy before going to receive the Most Precious Body and Blood of Christ? It’s heartbreaking… We have no sense of sin and little sense of unworthiness because man has made himself a god. We see more a sense of entitlement – even when it comes to the Eucharist. How many march up to receive Communion without having gone to Mass or confession in many years?

Response from David Tate:

We fall so easily into the trap of comparing the past with the ‘superior’ standards of today. The quotation that really helps me to refrain from unfairly judging the past is, “That was then, and this is now.” We must also include this mentality when understanding how the early Church celebrated Liturgy. It is very easy to ‘suppose’ many things. We can err on both sides of supposition. The first side is that because they were closer in time to the Apostles, they must have been more correct. The other side is to assume that they did a lot of “improvisation” due to their ignorance of a truly proper liturgy. Through research of ancient liturgies, Fr. Kolinski shows that the Early Church gained quite quickly a “striking uniformity… at a very early date.”

Fr. Kolinski often says that Heaven touches the earth during the Holy Mass. We are so accustomed to seeing with our eyes of flesh that it is difficult to perceive sometimes the difference between the Liturgy and any other human performance. If we had eyes to see the transcendent, our lives would be completed changed with a single Mass. How true it is when we see how the Old Covenant priests did celebrate a shadow of Holy Mass when they served at the Altar of the Holy of Holies.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed