by

Fr. Dennis Koliński, SJC

What few people within the Church seem to have considered, however, were the cultural, psychological, and theological implications of such a change in the orientation of worship. Within the context of ritual, the arrangement of church architecture is often very fragile and even relatively minor changes can dramatically change the symbolic messages that a church and its liturgy communicates to its members.

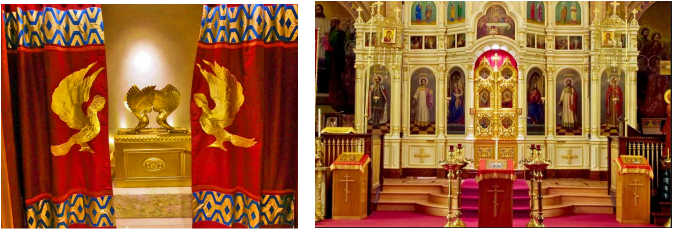

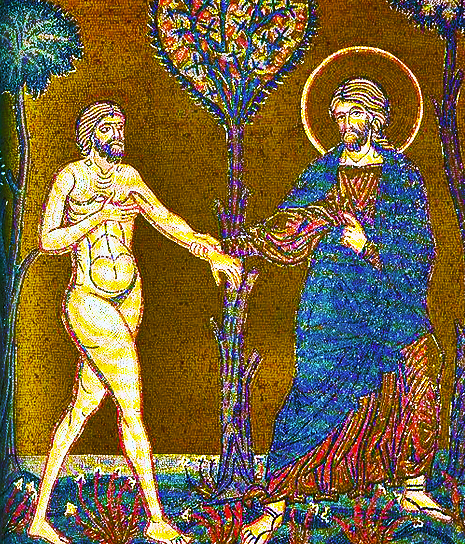

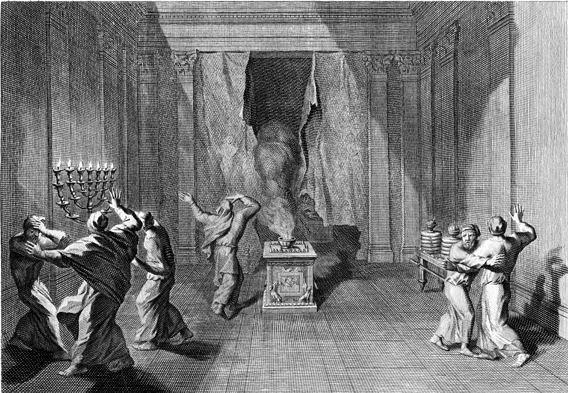

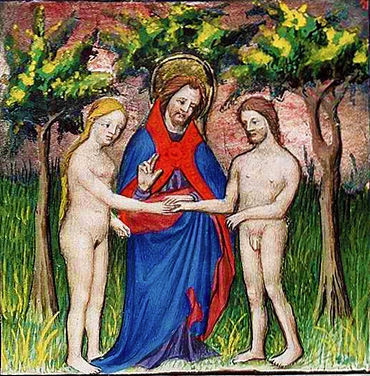

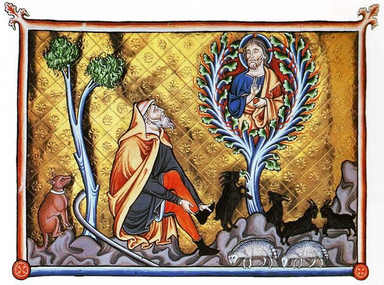

The orientation to the East--ad orientem—held a profoundly mystical significance for early Christians, but it also had roots deep in their Jewish traditions. As a fulfillment of the Old Covenant, the Christian liturgy and the spaces it used for worship were, therefore, a natural outgrowth of ancient Jewish practices.

Because the first Christians were Jews, the eastward orientation of prayer was a concept that was not at all foreign to their tradition, for they believed that Eden was located to the East. The rising sun was another image which conveyed the significance of this orientation: “the sun, which comes forth like a bridegroom leaving his chamber,” “the sun of righteousness shall rise,” and “his face was like the sun shining in full strength,” from the Old Testament, as well as similar passages in the New Testament referring directly to Christ: “his face shone like the sun.”

However, although the first Christians were Jews, the focus of their worship shifted from the presence of the Unseen God in the Holy of Holies to the anticipated Second Coming of the Incarnate Christ, which was represented by the East. We can see how this affected the orientation of their prayer in the most ancient type of Christian church found in Syria. While they were, in a sense, Christianized synagogues, they faced the geographic east rather than Jerusalem.

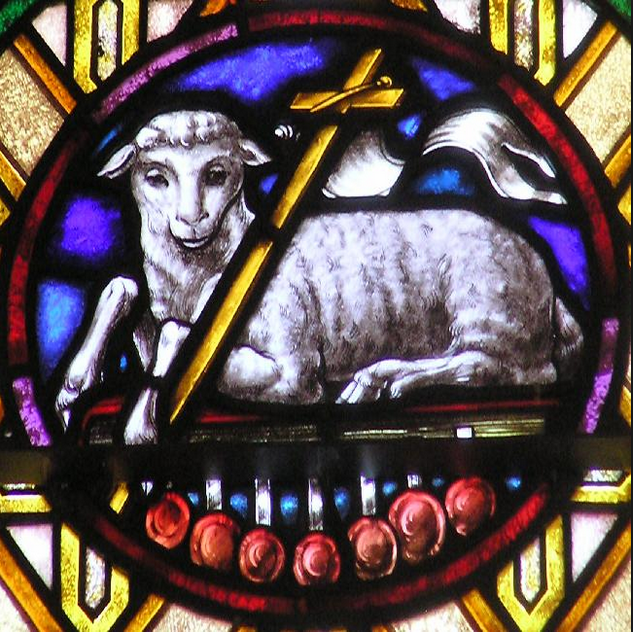

The early Christians adopted this practice of praying toward the East for a very profound reason. They oriented their worship in this direction because they believed that Christ ascended into heaven toward the East and that He would return again in His Second Coming from that same direction. Thus, by turning in prayer toward the rising sun, which symbolized Christ, they directed their worship not to the earthly Eden as the Jews had done earlier, but to the new Paradise in Heaven.

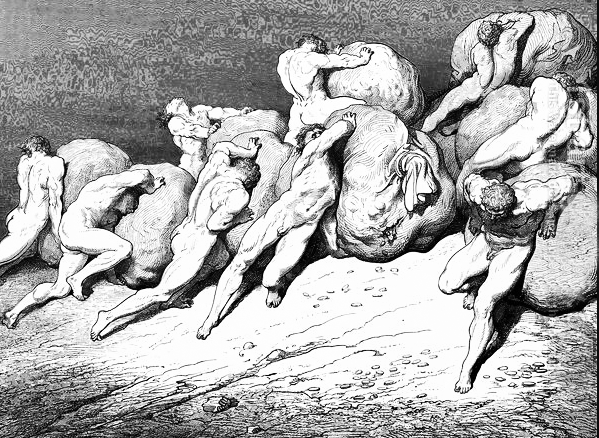

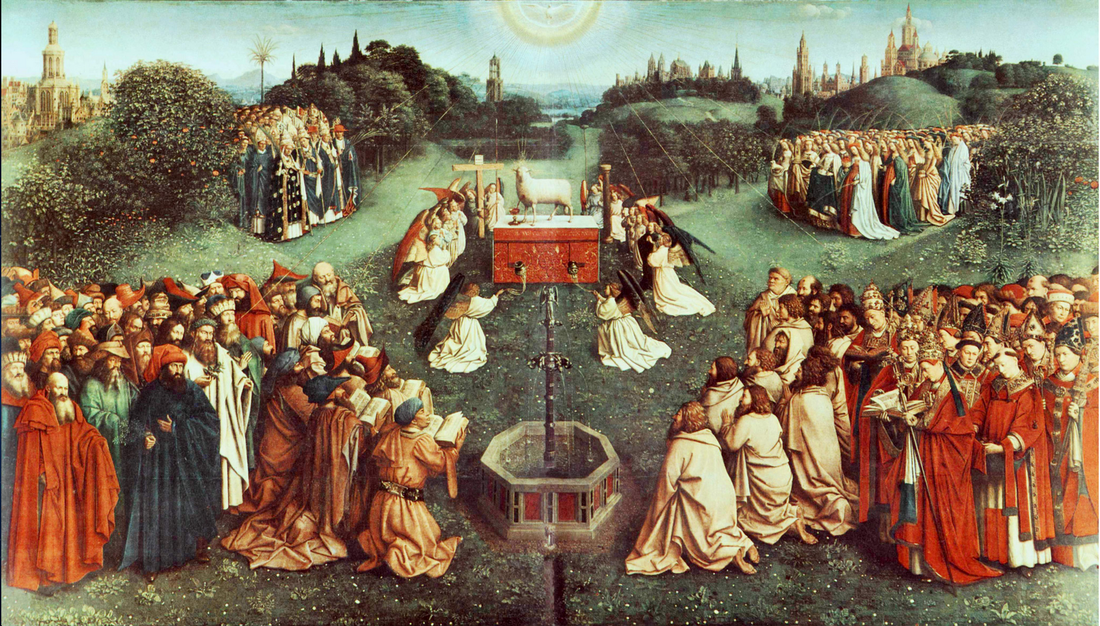

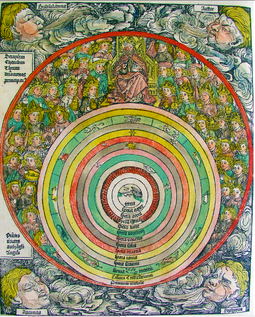

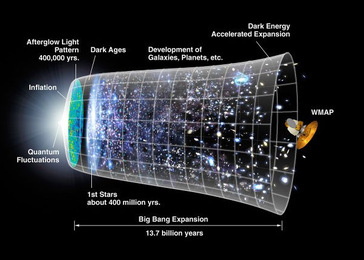

According to Cardinal Ratzinger, the East has always been “cosmic”—“The liturgy, turned toward the east, effects entry, so to speak, into the procession of history toward the future, the New Heaven and the New Earth, which we encounter in Christ.” In this ancient custom of facing East the church building itself was, so to speak, a ship (“nave” = navis, Latin for “ship”) that voyages to the East.

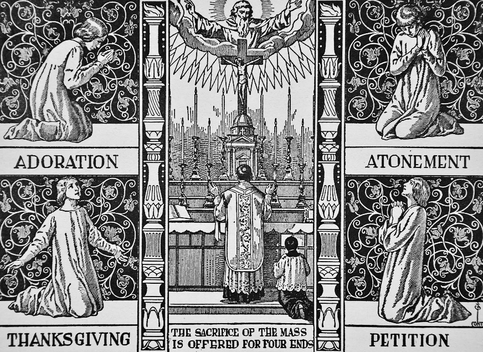

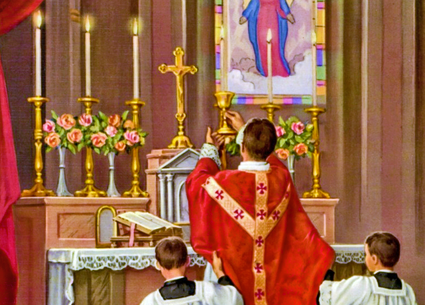

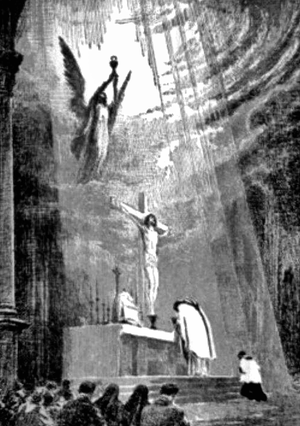

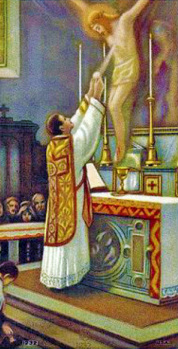

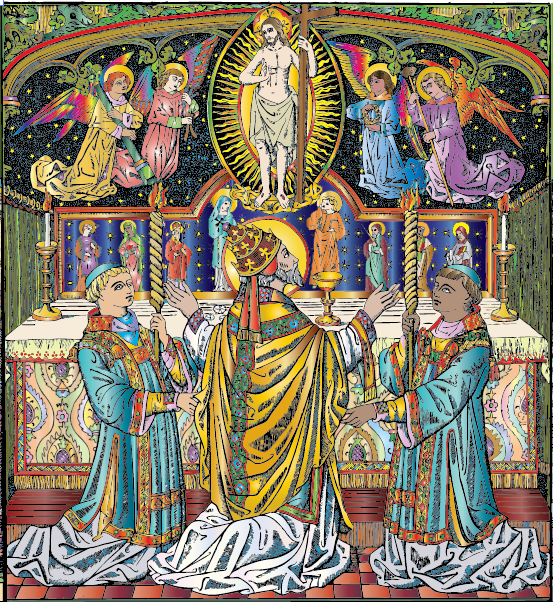

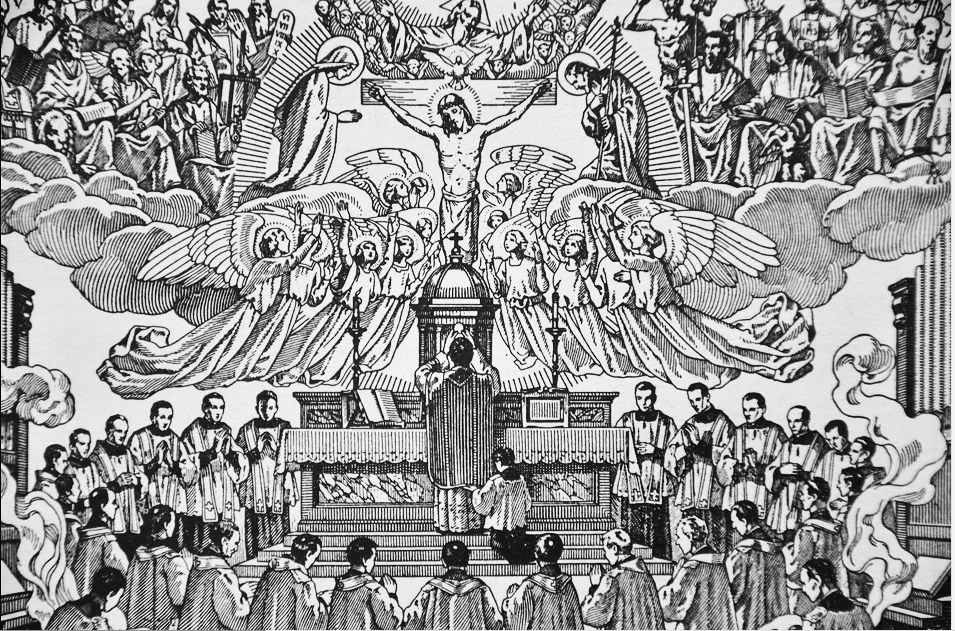

The eastern orientation of prayer, therefore, was the universal norm in the Church from the earliest years of Christianity. The altar, which generally stood in an apse at the eastern wall of the church, was the focus for the entire assembly. Both priest and laity looked toward the East in unity as if in procession because it was the gateway to heaven, their destiny. The altar was “the place where heaven is opened up” leading the church “into the eternal liturgy.” And it was because of the powerful symbolism embodied in this communal act, that neither the eastern nor the western Church had a tradition of versus populum. In fact, the term versus populum itself was unknown in Christian antiquity, for it was a concept foreign to their understanding of the Holy Sacrifice.

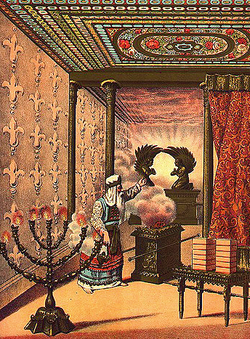

The Christian basilicas of Rome (e.g., St. Peter’s Basilica on the Vatican Hill) and northern Africa that came into use about the time of the Emperor Constantine were the only notable exceptions to the eastern orientation of Christian worship. In contrast to the churches in other parts of Christendom, as well as to many in Rome itself, they had the uncharacteristic practice of constructing the building with the façade, instead of the apse, facing east. Along the back wall of the apse were the bishop’s chair and seats for other clergy. The altar, which stood over the tomb of some important martyr, stood between the bishop (or priest) and the people. He stood behind the altar facing the doors of the church, which opened to the East, celebrating the Eucharistic Sacrifice in the universal Christian orientation. Likewise, the people gazed not toward the priest, but rather eastward with him. Although the priest technically stood versus populum, the intent was to face East rather than to the assembly.

This practice, however, was confined only to the immediate vicinity of Rome and parts of northern Africa, whereas in the remaining regions of Christendom the priest and assembly continued the ancient tradition of facing together toward the East. Even in the churches of Byzantium which trace their development from the Roman basilica, the altar stood in the apse allowing the priest to celebrate Mass from the same side of the altar as the people themselves so as to face East together.

Despite the erroneous assumptions underlying the versus populum orientation of the altar, the vast majority of Catholics today see it as the predominant fruit of the Second Vatican Council. However, what Catholics received were actually “dubious reconstructions of the most ancient practice, fluctuating criteria, and never-ending suggestions for reform.” And even if there had been legitimate historical justification, this would have represented little more than a “false antiquarianism”—something against which Pope Pius XII explicitly warned.

A strong case can be made for a return to ad orientem on purely historical grounds, but some might say that this is merely another type of “false antiquarianism”. However, when one also considers the theological, as well as cultural, sociological and psychological factors that both influence and are influenced by the highly symbolic nature of orientation at a ritual, the issue takes on a much greater importance.

We have seen how culturalism invades the liturgy, which makes use of it to legitimate and sanction certain values of our present culture, by often co-opting the liturgy in such a way that its original meaning is muted or lost. Architecture, of which the altar is an integral part, is a symbolic language in itself and ritual, which in turn is an outward expression of interior belief, then places an additional layer of symbolism over the physical components of the architecture. When one manipulates both of them the significance of the symbolism and even the very substance of belief changes. That is primarily why Cardinal Ratzinger has expressed the view that the symbolism of the priest as the one who offers the Holy Sacrifice in persona Christi on behalf of the people “is more clear and effective when the priest faces ‘liturgical east’—the altar of sacrifice—with the people.”

There are also strong cultural and psychological reasons justifying a return to the East. Because “the spiritual disease of modernity is the worship of ego,” the reorientation of the altar has resulted in a shift of focus in the minds of many Catholics from sacrificial worship to communal celebration. One of the greatest authorities on the Roman Rite of the Mass, Rev. Joseph A. Jungmann, SJ, seems to have foreseen this in his book The Mass of the Roman Rite, which he published long before anyone even thought of a Second Vatican Council. He wrote that versus populum would be a preferred orientation if the Mass was seen only (my emphasis) as a service of instruction or a Communion celebration but ad orientem would be the most appropriate orientation if it was seen as an immolation and homage to God.

Some of the most subtle but yet most detrimental effects of the versus populum orientation are the psychological and sociological consequences of this arrangement for both the priest and people. When the priest faced ad orientem, he was, in a sense, an anonymous mediator between God and man. Such an arrangement intrinsically hindered the priest from calling attention to himself. But, when turned versus populum, he became a distinct person with a distinct personality and the sanctuary became a stage, in which the altar turns him into an actor playing a role in the re-enactment of the Last Supper. Instead of creating a greater unity with the assembly, this has led to a clericalization where the priest stands separate from the people rather than with them. He is the new point of reference because everything depends on him. Consequently, the actions of mere humans becomes more important than the mystical action of Christ on the altar by means of the priest. The altar is no longer really the focus because it has become only a prop for the actions of the priest. What has happened is that we have forgotten that, “the church exists for the altar, rather than the altar for the church.”

If we speak about the essential character of the Mass, there is no question of its validity with either orientation. There is also no question that it is possible to celebrate the Mass versus populum as reverently and beautifully as the Fathers of Vatican II surely envisioned it—there are many places around the world where this is taking place free of liturgical aberrations. But if we delve into the deeper significance of the symbolism behind each, versus populum does not convey the same message as ad orientem.

Should the Church return to its theologically correct and historically universal orientation, to the East, in its celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass? The answer more and more convincingly seems to be “yes.” However, rather than the historical justifications so often expounded, the most compelling arguments can be found in the cultural and psychological significance that such a move would entail. In her book, The Desolate City, Anne Roche Muggeridge suggests that “the single most important liturgical ‘external symbol’ at the Mass is the position of the priest.”

Will it be difficult? Yes. Overcoming the ingrained cultural mindset that prevails among many (perhaps most) Catholics for our present Mass celebrated versus populum will be difficult. The most formidable task will be the total reeducation of the faithful about the profound meaning that the East should carry in the mind of Catholics, as well as about the very character of the Mass itself. However, if we are to truly renew the liturgy we must affirm by our very bodies that God, not man, is the object of our worship. The Christian liturgy is always a cosmic liturgy and when we forget this connection, it loses not only it significance but also its grandeur. We must, above all, strive for a profound restoration of the sacred in our physical enactment of the liturgy, where the Mass is not just a meal and a communal gathering, but rather the point at which heaven opens up so that we here on earth can share in the divine liturgy of heaven. And if this is best achieved by a return to the East, that is what we must do.

Sacrosanctum Concilium, 1.

Ibid.

The only directive in the Council documents which addressed the position and use of the altar merely stated that “the main altar should be freestanding, away from any wall, so that the priest can walk all around it and can celebrate facing the people.”(General Instruction on the Roman Missal, 262.) Elsewhere in the documents the Council Fathers issued an almost prophetic statement that “Nobody, therefore, is allowed to proceed on his own initiative in this domain [i.e., the sacred liturgy], for this would be to the detriment of the liturgy itself, more often than not,”( Inter Oecumenici, 20.) However, as they so often did, modernists within the Church disregarded such admonitions, and often interpreted Vatican II documents to suit their own needs.

Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal, The Spirit of the Liturgy (Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 2000), 34.

McNamara, Denis, “Church architecture and decorum,” Homiletic and Pastoral Review, 48/7 (April 1998), 10.

Gamber, Monsignor Klaus, The Reform of the Roman Liturgy: Its Problems and Background (Una Voce Press: San Juan Capistrano, California and The Foundation for Catholic Reform: Harrison, New York, 1993), 81. Kocik, Fr. Thomas M., “[Re]Turn to the East?,” Adoremus, 5/8 (November 1999), 5.

Psalm 19(18): 4-6

Malachi 4:2

Revelation 1:16

Matthew 17:2

Bouyer, Louis, Liturgy and Architecture (University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, Indiana, 1967), 11-15.

These early Syrian churches are known not only from archeological excavations, but also from traditions still maintained in Syrian Catholic and Nestorian churches. (Bouyer, Liturgy, 24.)

Ibid, 24, 27.

Gamber, The Reform, 81. Ratzinger, The Spirit, 68. Bouyer, Liturgy, 28.

Ezekiel 43:1-2

Ezekiel 43:4

Ratzinger, The Spirit, 69. Kocik, “[Re]Turn,” 5.

Revelation 7:2

Matthew 24:27

Ratzinger, The Spirit, 69.

Jungmann, Joseph A., S.J. The Mass of the Roman Rite, translated by Francis A. Brunner, C.SS.R. (Benziger Bro., Inc.: New York 1949), 180.

Ibid.

Hassett, Maurice M., “History of the Christian Altar,” Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. I (Robert Appleton Company, 1907), p. 6 from the Online Edition, 1999.

Ibid.

Kocik, “[Re]Turn,” 5.

Augustine, De sermone domini in monte II.18, PL 34:1277, from Gamber, The Reform, 80.

Bouyer, Liturgy, 55.

Ratzinger, The Spirit, 70-71.

Bouyer, Liturgy, 54. Gamber, The Reform, 77.

In northern Africa, this was closely tied to previous pagan practices of facing temple facades toward the east, which were incorporated into the construction of Christian churches. Kocik, “[Re]Turn,” 5. (from Jungmann and Bouyer)

Ibid

Jungmann, The Mass, 181.

Ibid. Bouyer, Liturgy, 62.

Bouyer, Liturgy, 82.

The ability to see everything that was happening at the altar has often been used as a rationale for the Second Vatican Council’s call for greater participation of the faithful in the Mass. Based on the flawed historical argument used to justify the versus populum orientation, it has often been assumed that Christians in the Early Church always participated visually in what the priest did at the altar. This too was not the case, for even in the early centuries of the Church a veil was usually drawn to conceal the entire sanctuary from view during the Canon of the Mass. In Roman basilicas the canopy surmounting the altar was probably a support for curtains that were drawn around the altar during the time of the Canon. Lucas, Herbert., “Ecclesiastical Architecture,” Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. V (Robert Appleton Company, 1907, Online Edition, 1999). Also, the practice of looking at the Eucharistic elements was unknown to Christian antiquity and even if the people could see what the priest was doing, there was not that much to see because the more ritualistic gestures did not come into use until the Middle Ages. “More generally, the concentration on seeing what the officiants do, far from having ever accompanied a real participation of all in the liturgy, has appeared as a compensation for the lack of this participation, and is psychologically more or less exclusive of it.” Bouyer, Liturgy, 57-58.

Rather, it was customary in the time of Christ for everyone to recline on the same side of the table. It was precisely the fact that he sat with them instead of opposite them that gave the meal its communal character. Ibid, 53-54.

Ratzinger, The Spirit, 82.

Kwasniewski, Peter A., “Traditional liturgy as a liberation from egoism,” Homiletic and Pastoral Review, 49/4 (January 1999), 23.

McNamara, “Church,” 10.

Ritual can also be the means by which one evokes that belief. Kwasniewski, “Traditional,” 26.

Hitchcock, “Bishop’s,” 3.

Ibid, 21.

Jungmann, The Mass, 182.

Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal, The Feast of Faith (Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 1986), 140-41.

Gamber, The Reform, 85-88.

These same dynamics have been contributing factors in feminist criticism of the “power” and “authority” held by the supposedly oppressive male-dominated Catholic clergy, which consequently plays a large role in the psychology of those demanding women’s ordination.

Interestingly, the Roman version of the GIRM warns against the appearance of a throne for the celebrant’s chair. The American version does not. Also, in the Roman version, the first item treated is the altar, whereas in the American version, it is the celebrant’s chair. Dimock, Giles R., O.P., “Will Beauty Look After Herself?” Sacred Music (Fall 1990), taken from The Catholic Liturgical Library website.

Ratzinger, The Spirit, 80.

Webb, Geoffrey, The Liturgical Altar (The Newman Press: Westminster, Maryland, 1949), 18.

Kocik, “[Re]Turn,” 5.

Ibid, 70.

1. What is the mystical significance of prayer facing east for Christians?

2. When offering Mass ad orientem why is the priest not standing “with his back to the people?”

Response from Tommie Kim, Post Masters’ Korean Student:

Some years ago, I was on a pilgrim trip to Italy specifically to visit the sanctuaries of Saint Padre Pio and Saint Benedict. When we arrived in San Giovanni Rotondo, we were able to attend the Mass facing East. For Koreans, the Mass facing East was very unfamiliar in the beginning. However, as the Mass progressed and we were reminded of the fact that, at one time, Saint Pio was always there throughout his entire life assisting mass facing East, I was brought to a deeper sense of mystery of Mass. The priest, after the Mass, also explained that he experienced the holiness of the Mass in an extraordinary way and was able to concentrate on mystery of the Mass without distraction. The priest said he felt in union with the people and realized the meaning of the tree, vine and the branches. Not just we pilgrims but people from all over the world attended the Mass.. I remember them mentioning that although the Mass was assisted in Korean, they felt it as an hour of sharing unity and peace in God.

Response from Kathleen Brouillette, Student at Holy Apostles:

We have not been taught the significance of the priest leading us to greet Christ upon His return, coming from the East. How can we care about the Mass being celebrated ad orientem in this culture that glorifies self unless we are taught why it was celebrated that way in the first place? Failure to help people understand what we do as Church and why we do it made it all the easier for man to focus on himself rather than God. We have seen the focus taken from God, not only in the orientation of the Mass, but also in language, architecture, music, and art. It isn’t about worshiping, glorifying and thanking God, it is about man expressing himself. What have all these changes done for our faith and worship?

The Early Church regarded prayer facing the East as an apostolic tradition that was an essential characteristic of the Christain liturgy. The 2nd book of Apostolic Constitution written in the 3rd century mentions that church should be build “with its head to the East.” So the eastern orientation of prayer was the universal norm and belief of the Early Church. From the earliest years of Christianity, Christians believed that it is from East that the direction of heaven that her Lord and Savior would return in glory because it is the gateway to heaven and their destiny. Also the historical liturgy of Christendom of the Early Church has always been cosmic. So for the Christian, God is the object of our worship and by facing, both priest and layman were able to worship her Lord and share the mystical liturgy of heaven together. Christian liturgy is always a cosmic liturgy so facing East for Christians is not just a meal and a communal gathering but it is the hour when heaven opens up so that we who are on earth can share the divine liturgy of heaven.

When offering Mass ad orientem, priest is not standing with his back to the people but actually priest and people are facing the same way towards East so that priest and people can worship God together. The priest is standing in front of people to offer the Holy Sacrifice in persona Christi on behalf of the people. According to Cardinal Ratzinger, ad orientem is more clear and effective when the priest faces ‘liturgical east’ – the altar of sacrifice – with the people.”

RESPONSES TO THIS CHAPTER:

Response of Sean Hurt:

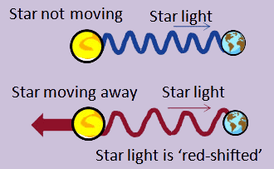

“The rising sun was another image which conveyed the significance of this orientation…”

The symbolism of facing east contains a deep meaning for humankind. Interest in the direction of East is not unique to Christianity. It’s a common element in world mythology. This illustrates the symbol’s potency to the mind. The sun is the physical source of light and life. It’s swallowed by the West and miraculously reborn to the East. You can see the parallels with our Savior. He is the spiritual source of our light and life. He’s invisible now like a nighttime-sun. We face the east, waiting for the second coming of the sun to end the spell of night.

In this ancient custom of facing East the church building itself was, so to speak, a ship (“nave” = navis, Latin for “ship”) that voyages to the East.

The symbolism of the church as a ship is interesting. Certainly, a ship calls to mind Noah’s ark. We can easily point out parallels. The ark preserved God’s chosen people for a new creation. It saved them as the church saves us. However, this is not a perfect type. Noah’s ark drifted sort of aimlessly. As the author mentions, we imagine our church journeying to the east to meet our Lord. We have an object—and end, versus Noah’s passive salvation.

We have seen how culturalism invades the liturgy, which makes use of it to legitimate and sanction certain values of our present culture…”

On a light-hearted note, I wonder if sometimes we don’t add –ism to the ends of words in order to set hearts against them. I mean, we could have replaced “culturalism” with a more familiar term: enculturation. Anyway, I want to add a nuance to the author’s discussion here. The relationship between culture and liturgy is complex. As the Catechism says, there are certain immutable aspects of the liturgy that cannot be changed and certain ones that can. In every age and in every place we protect the Light of Christ from the ephemeral values of our society. At the same time, Christian faith should not abolish the culture of the newly evangelized. In some instances, it’s necessary to change the accidentals of liturgy to jive with culture. I mean, in Malawi, they couldn’t comprehend divine celebration without dance. I just want to balance out the author’s warnings about culture influencing liturgy.

However, in the particular issue, I agree with the author’s concerns. As I commented before, Jesus placed great importance on symbolic thought. This is evident in his discussion with Nicodemus. When Nicodemus asks Jesus for a rational explanation of rebirth, he responds with “Amen, amen, I say to you, no one can enter the kingdom of God unless they are born of water and spirit.” Jesus tries to break this teacher of Israel out of the stale confines of materialistic thought. We should pause here for a moment and reflect on modern Western education. Do our schools emphasize symbolism as much as Jesus did?

I know perfectly intelligent, well-educated people say, “Oh, I don’t get poetry. Why don’t they just say what they want to say?” Now, we should be sort of shocked by this. In fact, we should be floored to hear such an opinion. For tens of thousands of years all of humanity has echoed a common symbolic language. The rising sun, the tree of life, the leviathan, the serpent, these were known on every land in every epoch. What happened to our society that huge swaths of educated people don’t value these things anymore?

Christians need to think symbolically; our salvation depends on it. We cannot rationally comprehend Revelation. Imagine the gospel, liturgy, prayer and sacred art without symbolism. They would be incoherent and the Mysteries would be nonsense. Symbols are the language of the soul, and it’s the soul that thirsts for Jesus.

We confront problems in the church, inevitably, with a certain bias in the way we think. There is a great danger here because the Western academic tradition does not value symbolic truth as it should. I think we must be careful removing symbols (such as facing East) from any aspect of the faith. We can’t rationally understand their full-meaning because they inform our consciousness in a hidden way.

Architecture, of which the altar is an integral part, is a symbolic language in itself and ritual, which in turn is an outward expression of interior belief…

As I mentioned before, I go to two different parishes. One is more contemporary, another more traditional. Just as the author states, I see the architecture of the altar expressed in liturgy celebration and the beliefs of the parishioners. At the more traditional parish, the massive altar sits center stage. The lectern, on the other hand, they situated off to the side. As I mentioned before, parishioners at this traditional parish bow and supplicate when the priest consecrates the host. The liturgy climaxes in the Eucharist. I noticed too that priests there unwaveringly endorse the notion of transubstantiation.

At the contemporary parish, the altar stands side-by-side with the lectern. As I noted before, the mass does not climax so definitively in the Eucharist. More emphasis is placed on the homily. The architecture of the altar echoes this diffused emphasis.

Response from David Tate, seminarian at Holy Apostles:

My favorite reference when describing aspects of a Church is described by Fr. Kolinski when he adds that while facing the East, a Church should have the appearance of a [long] “ship heading into the East” with the priest in the lead guiding the people to the coming Christ.

… This discussion can offer several understandings of what is intended by, “Why the priest is not standing with his back to the people?” The first version of this question should remind us that the priest does not always face in the same direction during the Mass. Sometimes, he is facing the Altar as a true priest standing at the Altar. Other times, he turns intentionally to the people in order to address or pray for the people.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed